When Matilda the Musical opened in Stratford-upon-Avon in 2010 – quickly moving to the West End, where it still resides – the British press greeted it as an “anarchically joyous, gleefully nasty” antidote to the sugary concoctions of other kid-centered musicals.

(That reference to Stratford, by the way, isn’t a misprint. The show was commissioned and premiered by the Royal Shakespeare Company, which occasionally strays from the classics and even into musical-theater territory. A little number called Les Misérables was also their doing.)

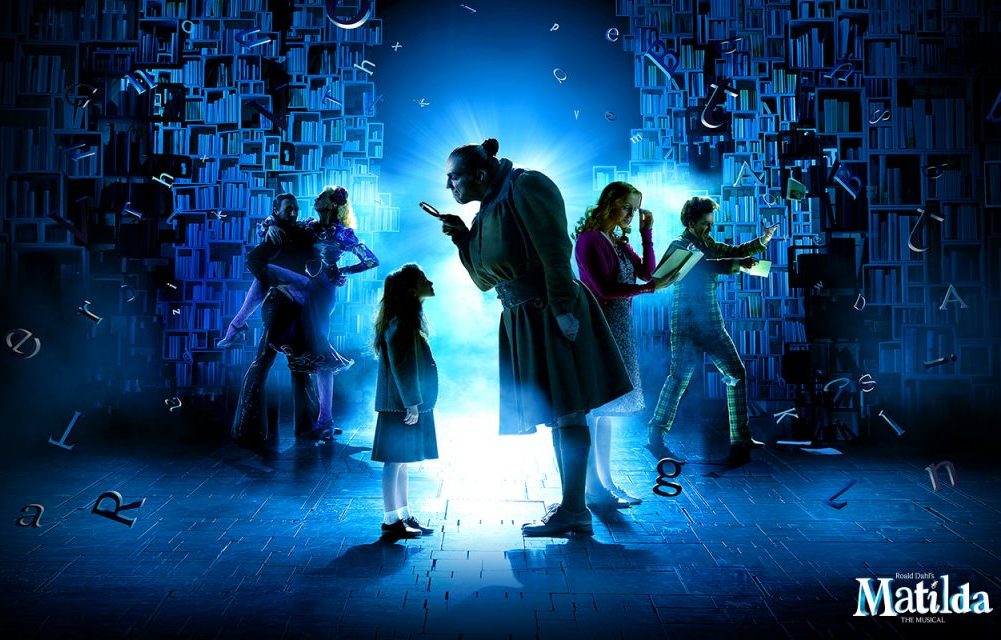

Based on the children’s book by Roald Dahl, Matilda the Musical begins with Matilda’s unwelcome b irth – which annoyingly inconveniences her ballroom-dancing mother and infuriates her father because she’s not a boy – then fast-forwards to her schooling in the Dickensian Crunchem Hall (motto: Bambinatum est Maggitum, i.e., Children are Maggots), presided over by the sadistic and well-muscled Miss Trunchbull.

irth – which annoyingly inconveniences her ballroom-dancing mother and infuriates her father because she’s not a boy – then fast-forwards to her schooling in the Dickensian Crunchem Hall (motto: Bambinatum est Maggitum, i.e., Children are Maggots), presided over by the sadistic and well-muscled Miss Trunchbull.

The thoughtful little girl has a voracious appetite for reading (one of the show’s, and the book’s, implicit aims is to promote a love of literature) as well as an off-the-charts IQ and a knack for telekinesis. It’s the latter gift that permits her to rescue both her classmates and her sympathetic teacher, Miss Honey, from the headmistress’s merciless clutches.

The premise parallels both Oliver! and Annie, as well as Dahl’s perennial themes – hapless children bullied and bruised by callous grown-ups. And while Matilda isn’t technically an orphan, she might as well be, with knuckleheaded parents who are indifferent or hostile to her and contemptuous of her intellectual bent.

But where perky little Annie sings dreamily of a hopeful tomorrow, po-faced Matilda recognizes that “Just because you find that life’s not fair it / Doesn’t mean that you just have to grin and bear it.” And where Oliver’s fellow urchins sing cheerily of “Food, glorious food,” Matilda’s schoolmates ultimately rebel, in a rock’n’roll-fueled uprising, turning the tables on one of Miss Trunchbull’s favorite epithets: “We are revolting children!”

But where perky little Annie sings dreamily of a hopeful tomorrow, po-faced Matilda recognizes that “Just because you find that life’s not fair it / Doesn’t mean that you just have to grin and bear it.” And where Oliver’s fellow urchins sing cheerily of “Food, glorious food,” Matilda’s schoolmates ultimately rebel, in a rock’n’roll-fueled uprising, turning the tables on one of Miss Trunchbull’s favorite epithets: “We are revolting children!”

Tim Minchkin’s music and lyrics are harder-edged and wittier than either of their musical forebears’, and Dennis Kelly’s script, true to Dahl’s unsentimental vision, keeps open the possibility of an unhappy ending before (sorry for the spoiler) heading into the final happy one. Which I find deeply satisfying in a show.

So it’s painful to report that I didn’t find the touring production of Matilda the Musical, now playing at the Bushnell in Hartford, all that satisfying. I hadn’t seen either the original or New York versions, but I assume this one is a photocopy of those, since the creative teams are the same: director Matthew Warchus, choreographer Peter Darling, sets and costumes by Rob Howell.

This show has been on the road for ten months, and to me the performance felt more than a bit mechanical. The ensemble of singer-dancers went through their paces precisely and energetically, but I saw mostly the precision and energy without the enthusiasm. Oddly, and encouragingly, the corps of children gave more heart to their numbers than the grown-up choristers did.

All, that is, except Lily Brooks O’Briant, one of three youngsters who rotate in the title role. She and the other two, Sarah McKinley Austin and Savannah Grace Elmer, have been with the show since the beginning of this year, and I have no idea what her co-performers are like on stage, but on press night in Hartford, O’Briant was literally going through the motions.

Matilda is meant to be impassive – a self-contained tyke who lives in her head and rarely smiles. But O’Briant was simply passive, dutifully executing her routines, at times almost visibly counting off the measures before the next gesture, and wearing the same blank expression no matter what was going on inside or around her. I don’t blame this nine-year-old for the robotics, but the director and her coaches, for allowing her such an inert performance and assuming (correctly, judging from the curtain call ovations) that the audience would be carried away by her sweetness and stamina.

I was also disappointed by David Abeles as Miss Trunchbull. The part is in the classic tradition of the pantomime dame – a man in outrageous drag outrageously playing a mannish woman. It’s perfect for the musical’s version of the character, a former Olympic hammer-throwing champion. She needs to be scary, ridiculous and funny, but Abeles makes her little more than a smirking brute.

I was also disappointed by David Abeles as Miss Trunchbull. The part is in the classic tradition of the pantomime dame – a man in outrageous drag outrageously playing a mannish woman. It’s perfect for the musical’s version of the character, a former Olympic hammer-throwing champion. She needs to be scary, ridiculous and funny, but Abeles makes her little more than a smirking brute.

Of the other leads, I particularly enjoyed young Ryan Christopher Dever as the fat boy who’s forced by Trunchbull to eat an entire cake and later leads the students’ revolt, and Quinn Mattfeld as Matilda’s crooked car-dealer dad, a smarmy Cockney who boasts, “All I know I learned from telly.” (The program includes a glossary of English terms that might be unfamiliar to Americans who don’t watch Masterpiece and Mystery on the telly.)

Matilda the Musical plays at the Bushnell, 166 Capitol Ave., Hartford, through this weekend.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com