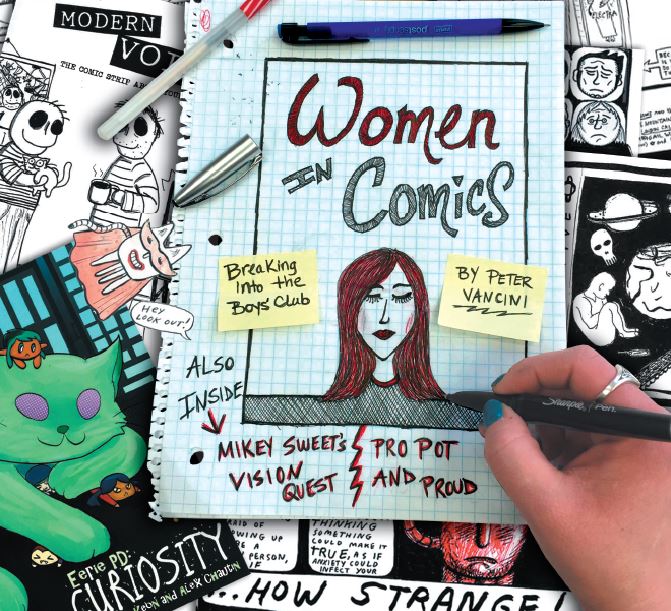

When Melissa Lewis-Gentry walks into a comic book store, it’s not to shop for her boyfriend or her dad. Still, she’s sometimes received that way, despite being the manager of a comic book store herself.

Once regarded exclusively as the fodder of wide-eyed grade-school boys and the secret indulgences of young-at-heart escapists, comics were once widely derided by “responsible adults” as prurient rubbish. But the medium has undergone a renaissance over the past decade or so, as comics — and graphic novels, their thicker, loftier cousins — have gained mainstream acceptance, even landing a place on the shelves of public libraries and required reading lists for college courses.

As mainstream attitudes toward comics have changed, so too have the faces at comic store checkout counters — on both sides. Women are coming out of the nerd culture woodwork in droves to attend conventions, game nights, and other comics-related events. According to a social media survey presented at an ICv2 conference in 2014, women now make up nearly 50 percent of comic book consumers.

But to say that women have been warmly welcomed into the comic book community would not be entirely accurate. Lewis-Gentry, who manages Modern Myths in Northampton, says that comic book stores have historically been a boys club and many remain a toxic environment for outsiders. Women like her, she says, are still routinely harassed at conventions. The majority of the discrimination though, is passive stereotyping.

“Most of it is this ‘gatekeeping’ and ‘cred checking’ that happens when walking into a store,” Lewis-Gentry says. “And there are some comic stores that would not even greet me or ask if I was looking for anything. Or if I was looking for something, they’d be like, ‘Oh, are you shopping for your boyfriend?’”

But hang all that, because women and comics go together like cheddar and apple pie — it’s wonderful and amazing, even if some pie traditionalists consider it to be weird. And in the Pioneer Valley, women aren’t just reading, sharing, and talking about comics — they’re getting organized and creating their own.

Lewis-Gentry may be a mild-mannered store manager by day, but by night, she’s a Valkyrie. Well, to be fair, she’s a Valkyrie by day too, because the Valkyries are an association of women that work in comic book stores. They were organized three years ago by a dozen or so women as a way to showcase their pride and to create an online community to “fangirl out” about comics, as Lewis-Gentry puts it. By the end of 2015, the group had surpassed 500 members. While this is certainly an impressive growth trend, Lewis-Gentry is quick to point out that their numbers still seem extremely small when taking into account the thousands of comic book stores that exist in the U.S. alone. She and others like her are working hard to make sure that comic book stores are a welcoming, all-inclusive space. She even leads a popular monthly “Queers in Comics” discussion group at the shop.

The Valley has been a hotspot of comic culture since the days of Mirage Studios (of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles fame), Kitchen Sink Press, and the Words and Pictures Museum. A lot’s changed on the scene since those early days: from the content to the creators to the way comics reach their audience. Easthampton is widely perceived to be the epicenter of the webcomic universe at the moment.

Comic art is open to anyone who cares enough to put pencil to paper, and artists are flocking to comics by a wide variety of avenues. Here are three women in the Valley who are making their own comics:

Phoebe Helander Berkel studied fine art, with a focus on painting, at Hampshire College. She’s the author of the weekly webcomic “Tabby & Gom” and the print zine-style comic “Perspective.” She’s also the founder of the Florence School of the Arts, where she teaches comic creation, among other things, to young artists.

“I got started by accident,” she says. “I’m not someone who grew up in the comics world reading superhero comics or anything like that.”

Yet Berkel found that the medium lent itself well to the creative soul-searching she was undertaking. A few quickly-drawn images to accompany the words streaming from her mind to the page resulted in an unexpected treasure trove of ideas and the chance to free her mind and indulge her creative passions — as she puts it: “all the things I like to do happen at once.” She began holding herself to weekly deadlines, even when she didn’t have ideas. Letting the idea unfold, and sometimes letting the drawings inspire the writing, can produce unforeseen results.

“I think that [in] doing a weekly comic,” she says, “most of the time you have to come up with something when you don’t have an idea, and that’s when some of the most interesting things happen … When I don’t have something that I’m really trying to work out, something else happens, and that’s interesting, too.”

Berkel’s comics deal with deep philosophical topics about the nature of existence, the meaning of life, and the small wonders that make the world beautiful. She sees creating comics as a healthy and therapeutic way to empty her mind.

“My best work happens when I’m at the laundromat,” she says. “I’m mostly self-employed, so I always have a lot that I should be doing and a lot that’s distracting. When I’m at the laundromat, it’s really relaxing because there’s nothing else that I should be doing.”

Madeline LaPorte, similarly, found a home for her brand of offbeat gallows humor in the panels of her print and webcomic “Modern Voids,” the self-proclaimed “comic strip about your life” which lays bare the maddeningly funny ironies of the modern life. She’s a cartoonist, she says, careful to differentiate between her work and that of comic book artists. She grew up reading the work of Berkeley Breathed, Gary Larson, and Bill Watterson. She credits doodling comics during class with “getting her through” public school. Having spent much of her young adulthood in customer service jobs, it’s an outlet she continues to rely on.

“The cool thing about being a cartoonist,” she says. “Is that there isn’t anything that anyone can do to me that I can’t make fun of later. And that’s why having bad customers is kind of a blessing sometimes, because you’re like, ‘Thank you, sourpuss old man, for giving me the inspiration to create a cartoon’ … I guess it’s a way of coming home and releasing everything that you can’t say. That’s what a lot of cartooning is.”

LaPorte is active in the local music scene, too, frequently performing at local venues solo or with a band, which she says helps her achieve a balance between the inherently lonely nature of comic creation and the desire to collaborate creatively with others.

“In terms of a community of artists,” she says. “It’s a lot easier to find that with musicians because we’re all out and about like ‘Hey, this is what I do!’ so in that sense, trying to find a scene for cartoonists was a little harder to me, because first of all to be a good cartoonist it takes a lot of isolation. … It’s the opposite of music in that way… And the art itself [Modern Voids] is holding up a mirror to society and saying ‘Look how ugly it is out there. I don’t want to go out there.’ … It’s an introvert art form.”

Anne Thalheimer is arguably the most iconic female figure in the Valley comic book community. She’s been publishing her autobiographical comic “Booty,” a thinly-veiled public diary in comic form, for over 20 years, so comics have long been at the center of her personal and artistic life. She recalls, with a degree of embarrassment, her delight at binge-reading the “Tales from the Crypt” series as a kid. But her tastes broadened, and soon she was consuming every comic she could get her hands on. Eventually she’d write both her master’s and doctoral theses on comic books.

Thalheimer’s high school experience, she says, was a miserable one. So when she was allowed to leave to attend Bard College at Simon’s Rock, an early college program, she felt she had finally found her home.

“I was a weird kid and really stuck out at my high school,” she says. “Then I went off to [Simon’s Rock] and it was like landing on my home planet, where I got to meet other freaks and weirdos who were into The Cure and all kinds of other things, and I was finally like, okay. There is good in the world. There are people that are like me.”

But that happiness was not untouchable, as Thalheimer learned tragically. During her second year at the college, a gunman killed two of her fellow classmates in a campus shooting. Since then, Thalheimer has struggled to come to terms with the experience.

The school shooting at Sandy Hook in 2012 — 20 years to the day after the incident at Simon’s Rock — was the final push Thalheimer needed to write the book that had been stirring within her since that fateful day. In 2013, she published “What You Don’t Get,” her personal memoir on growing up as an outsider and the search for reconciliation in the wake of the tragedy.

“It was the big secret,” Thalheimer says. “How do I tell people that I lived through this terrible thing and accurately convey it both as this horrifying thing that happened, and [also that] I would not be who I am without it? I wanted to set it in a broader kind of narrative and discussion about tragedy, because the reality of living in the United States now is that lots of people have a similar kind of story, but nobody’s talking to each other about it. We don’t know how to talk about it … At the same time, it’s necessary to talk about these things.”•

Peter Vancini can be reached at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.