By Hunter Styles

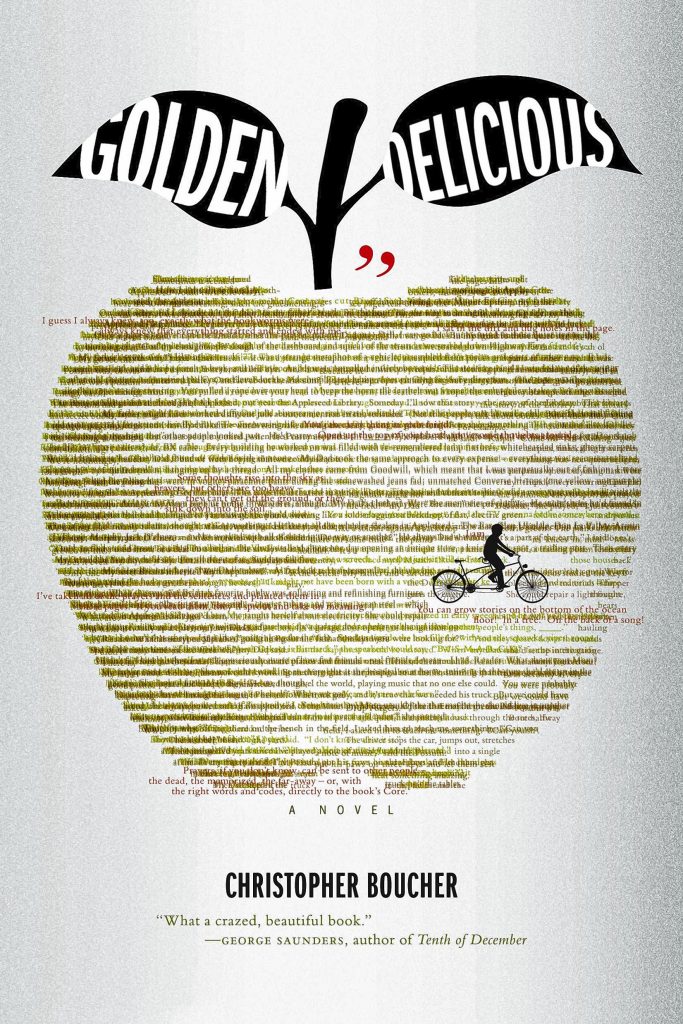

Welcome, reader, to Appleseed, Massachusetts. Never heard of it? On page one of his newly-released second novel Golden Delicious, Longmeadow native Christopher Boucher provides an off-kilter lay of this fictional land:

“That afternoon I took the Reader to see the Memory of Johnny Appleseed. We left right after school on my customized Bicycle Built for Two, the Reader on the back seat and me on the front. We pedaled through the paragraphs of downtown and across Highway Five to the deadgroves near the west margin, where I figured we’d find the Memory planting stories in the soil.”

This is a world in which the living spirit of books and storytelling is split weirdly, beautifully, open. Ink rises from the ground. Characters’ thoughts carry literal weight as cute, wriggling things. Untold stories grow in rows, sun-ripening page by page. Discarded punctuation manifests as debris. Told from the perspective of a child in a troubled family, Golden Delicious is a soulful successor to The Phantom Tollbooth. After feasting on this book for a few sittings, your brain is bound to be doing syntactical backflips.

Boucher, a former Daily Hampshire Gazette arts writer, lives and teaches in Boston now, but on the phone a few weeks ago he told me that his heart is still in Western Mass. On Wednesday May 4, he reads from Golden Delicious at Broadside Books in Northampton.

How does one go about writing the kind of book no one has ever read before? Here’s my conversation with him, edited and condensed for clarity.

Hunter Styles: Much of Golden Delicious is strange and otherworldly, but for Valley readers, it will also feel very local, with many references to area towns and businesses. How did you come to strike this balance?

Christopher Boucher: For Golden Delicious, I was writing stories that found a root in truth and my childhood, but that took surreal and fantastical turns. So, I was amassing vignettes and stories that I thought were interesting in their own right. But at first I didn’t know how they cohered.

Then I discovered that Johnny Appleseed lived in Longmeadow, where I grew up. I had no idea, even though he’s a folk hero. But it was just the thing I was looking for — this element of myth. All of a sudden, I had this character: the Memory of Johnny Appleseed. That allowed me to place these hometown stories in a fun context.

Hunter: It’s fun to read people’s attempts at describing your writing style. I’ve seen the words “zany” and “oddball” used in reviews. I believe one writer used the word “insane.” What do you think of these takes? Do they ever hit the nail on the head, or is it all for naught?

Chris: When I’m focused, I’m not chewing on any of these words. Trying to write something zany doesn’t work for me, although it might work for some writers. I think my humor tends to come out when I’m dealing with something that’s serious and I need to break it, crack it somehow. It’s an outcome, rather than a starting point.

I really found my road into Golden Delicious because I wanted to write about a particular part of my life, and I did it in the only way I know how. Maybe it came out a little zany. But I think that’s because of my interest in language, and my attempt to give the reader something that neither of us have seen before.

Hunter: There’s a lot of wordplay and inventive language in this book. And that playfulness produces some amazing visuals, like the image of the family’s house rising from the ground and walking up the highway on its own legs, carrying them to a new town. Do these notions start as a picture in your head? In other words: Do you see it, then write it — or see it after you write it?

Chris: I’d say that it starts as sound, actually. There’s an experimental writer named Ben Marcus who said that he writes like a failed scientist. When I heard him say that, I thought: I want to write like a failed musician. I have this great interest in sound, and I play music as a hobby. If anything gets me to the page, it’s the sound of words. I’m interested in the fact that the sound of a word hits you before its meaning does. So, I listen first for the sound. If I’m intrigued, and I want to keep going, then I think the reader does too.

Hunter: Your first book, How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, has fantastical themes as well — it’s about a single dad whose son is literally a 1971 Volkswagen Beetle.

Chris: Yes, I wrote that while I was living on Crescent Street in Northampton. That book took me about ten years to write, and I didn’t think it was going to get published. But I wanted to give it my all.

Hunter: Once that book was picked up by Melville House and met with some success in 2011, you had to write your next one more quickly. What was that like?

Chris: Melville House has been incredibly supportive over the last five years. I had the room to write a second book that took risks and tried new things, but I also had encouragement in my corner. That said, it was a little breakneck sometimes. I wanted to keep my ambitions as big as possible but still stay timely and meet my deadline. I’d like to think writing a first novel helped, so that I could recognize some of the bends in the road when I hit them.

Hunter: I read an interview with you about your first book, right when it was coming out, where you said that you were afraid that you had written “an impossible book.” Has your perspective on that changed? Does that fear persist?

Chris: I worried that I had written myself into a corner with the Volkswagen book. I had just been working on it for so long. This time, I was working with a publisher and thinking in real terms about how it would see the light of day. That’s where the character of the Reader comes from in Golden Delicious. When I had an anxiety about the text, I just named it in the text. The Reader is skeptical and asks questions. If the reader was going to have a tough time in places, I wanted to put a version of the reader in the book that could give voice to that.

Hunter: In some ways, Golden Delicious reads like a web of very short stories.

Chris: I always think in short pieces. I’ve published a few short stories, but a lot of the time, when I start out writing them, I don’t really know what they are. Sometimes, they lean on each other so much that they can start to become a novel. This time, I thought it was sensible to build on that tendency. If I think small, I’m able to take the risks that excite me.

I’m much more comfortable with five or ten pages at a time. For some reason, I think in those terms. Which makes the big-picture project feel like a catch-as-catch-can proposition sometimes.

Hunter: It seems a lot like planting seeds, actually. Maybe apple seeds.

Chris: Yeah! Sometimes you put something down and you don’t know what you’ve done. Then you come back to it weeks or months later, and it’s almost something different, as if it’s blossomed.

Hunter: In grad school at Syracuse, you studied with George Saunders, who’s also an experimental writer and novelist.

Chris: He was just fantastic. In my second year in his workshop, I brought in this weird story with lists of strange words and fantastical elements in it. I knew from minute one it wasn’t working. He and the other writers and I talked about it for an hour. I thought: experiment failed. But on the way out the door, George said to me: that’s just the committee talking. If you like what you’re doing, you should keep doing it. And he leads by example. His own writing has evolved so much over the years, and he keeps taking risks.

Hunter: Junot Diaz was there at that time, too, right?

Chris: Diaz is amazingly bright. Every time he writes, I see him do something I’ve never seen before. While I was at Syracuse, he was writing The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. He’d published Drown in 1996, but then 11 years went by. My grad school friends and I were wondering: what’s he working on? Turns out he was writing a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. That’s a good lesson I took from Junot and George: it’s all about the work. Sitting down at a blank screen and putting words on the page. Doing that over and over again, and being humble about the fact that it’s a difficult thing to do. I struggle with it as much as my students do.

Hunter: You teach at Boston College, right?

Chris: This is my seventh year at BC. I teach fiction writing and a variety of Lit courses. One Lit course that really took off is called “Walking Infinite Jest.” That book is set in Brighton, so we all walked that setting together and read Infinite Jest.

There’s good evidence that David Foster Wallace was writing from his own experience in some way. For a while, with Golden Delicious, I needed to be reminded of that potential — that I could go back to a blueprint of my family, and amplify it and distort it. There’s something rich and energizing about that.

Hunter: How do you think of your responsibility to your writing students?

Chris: At the undergrad level, most don’t necessarily come in with projects that they’re already working on. One of my missions, as I see it is, is to give my students a clear sense of contemporary literature beyond Stephen King and J.K. Rowling. George Saunders and Junot Diaz have come to campus. Karen Russell was here a while back. These are chances for me to say to my class: writing is something that people do every day, sometimes full-time. But even if you have another full-time job, that doesn’t mean this isn’t a great way to spend your time.

I ask them to write every day. And every week, I start class by asking them how many days they wrote. My own college advisor told me: if you lose one day, you lose two. So I try not to lose any days.

Hunter: Does your own experimental writing style and tastes affect the lens you bring to reading your students’ work, for better or worse?

Chris: My job is to be receptive. Students should write what they need to write, and our job as workshop readers is to meet that work on its own terms. Certainly George Saunders writes things that could be considered wacky or insane, but one of his favorite writers is Chekhov. Good storytelling is bigger than postmodernism or surrealism. And a lot of the writers that have been most instructive to me cross over those lines all the time: Calvino, Borges, Pynchon, Vonnegut. I’d be doing a disservice if I only steered people in my direction. Students need to steer themselves, and have the faith to do it. You have to take the voice you’re given, and push it.

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.