Those who worried about accidents at the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant causing environmental and health hazards severe enough to affect its downwind neighbors in Franklin County have less to worry about now.

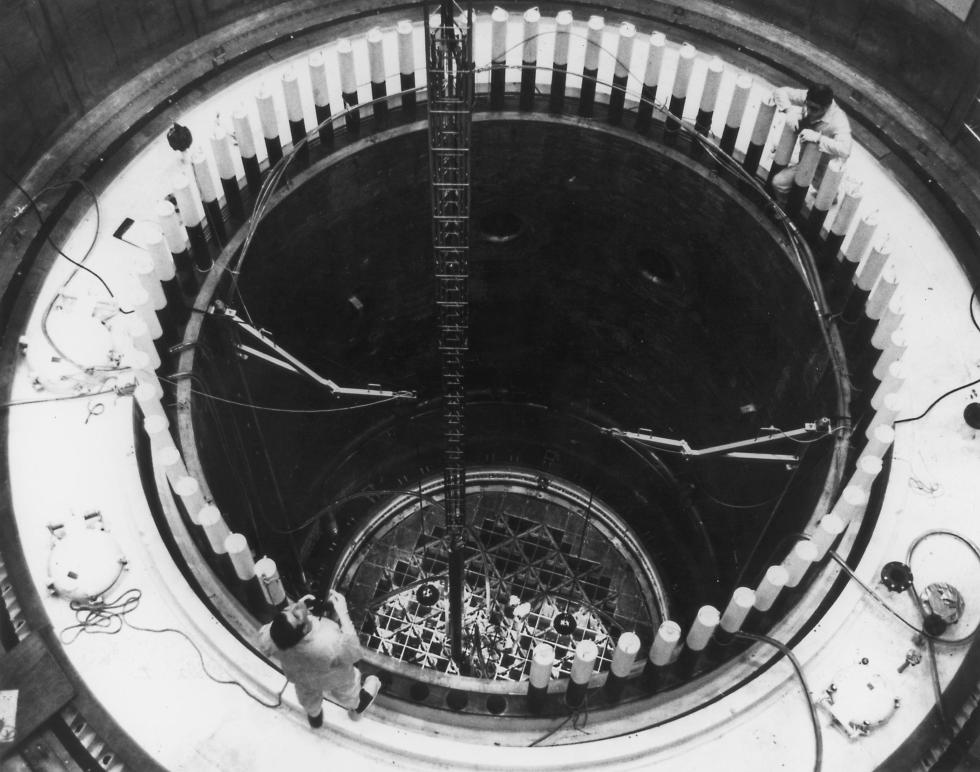

For about a year now, the 42-year-old, 620-megawatt boiling water reactor has been shut down, which greatly lessens the chances of any sort of significant problem that would breach the plant’s containment systems.

Consequently, the owners of the plant located just over the Northfield border in Vernon, Vermont, have sought and gained federal approval to discontinue its extensive and elaborate emergency planning zone within a 10-mile radius of the plant. The zone included the county’s northern tier of towns, including northern Greenfield. For years the plant’s owners, now Entergy, spent millions planning for warning and evacuating tens of thousands of residents in the tri-state area in the event of a major or catastrophic accident in Vernon.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission says now the plant will maintain an on-site emergency plan and response capabilities, including continued notification of state government officials of an emergency. The decision will allow Entergy to cut staff from 300 to 150. And save millions.

The NRC based its decision on the “reduced risks of accidents that could result in an off-site radiological release.” Apparently the greatest off-site danger comes from the possibility of a failure to keep the hot spent fuel rods sufficiently cool. If the closed plant’s cooling systems failed, the spent fuel could cause a meltdown that might let radioactive material to escape beyond the plant site.

The NRC decision eliminates the requirements that Vermont Yankee maintain formal off-site radiological emergency plans and reduced the scope of the on-site emergency planning activities.

But Vermont state officials want more, at least until all the highly radioactive spent fuel rods now tightly packed in a pool of cooling water inside the reactor building are transferred to dry casks to be located on the site outside the plant. A Vermont Public Service Department official agreed the danger of an accident has lessened, but still wants a somewhat reduced emergency planning effort to remain until the fuel rods are permanently moved to the casks of concrete and steel in four more years.

The state of Vermont may still appeal the decision.

We concur with our northern neighbors, especially because many of our county residents are closer to the potential problem than many in Vermont. Better safe than sorry.