After a long Sunday spent following Bernie Sanders on the campaign trial, I made a bet with my editor: 20 bucks says that man never kisses a baby on camera this election season.

She took the bet, but I’m going to win. Why? For the same reason Sanders is not going to don a flight suit or pop out of a tank anytime soon. The cantankerous Vermont senator is allergic to pandering. He may be pleased that you support him, but he’s not going to pat you on the back for it. He’s too busy trying to build a revolution.

Some of us used to say that George W. Bush, for all his faults, would be a good guy to get a beer with. I say, add that to the list of things you won’t catch Sanders doing. He is fired up, and his speeches have heat, but his persona is hardly warm. At 73 years old, he speaks with conviction about the corruption and failings of the American political system. Pay attention, he says — now is the time for real, imaginative change.

Sanders — the junior senator from Vermont and the longest-serving independent in the history of the U.S. Congress — announced his campaign for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president on April 30. He has been on the road often since then, criss-crossing the country and building grassroots support.

His popularity has surged in recent months as auditoriums and town halls fill with people eager to hear him speak. This “Bernie-mentum,” as some news channels have put it, makes Sanders the principal challenger to front-runner Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. A WMUR Granite State poll released this month found support for Sanders is at 36 percent among likely voters, compared with 42 percent for Clinton.

How has this stubborn, irascible democratic socialist built up such a head of steam in the primary race? That’s what I came to find out on this busy Sunday — at this rally, and then at two more New Hampshire rallies later in the day.

The answer, I think, is simple. Just watch the crowds, and see how they “mmm” and sigh, smile and nod. He is our stubborn, irascible democratic socialist. He is upset, and he is tired. Like a lot of us.

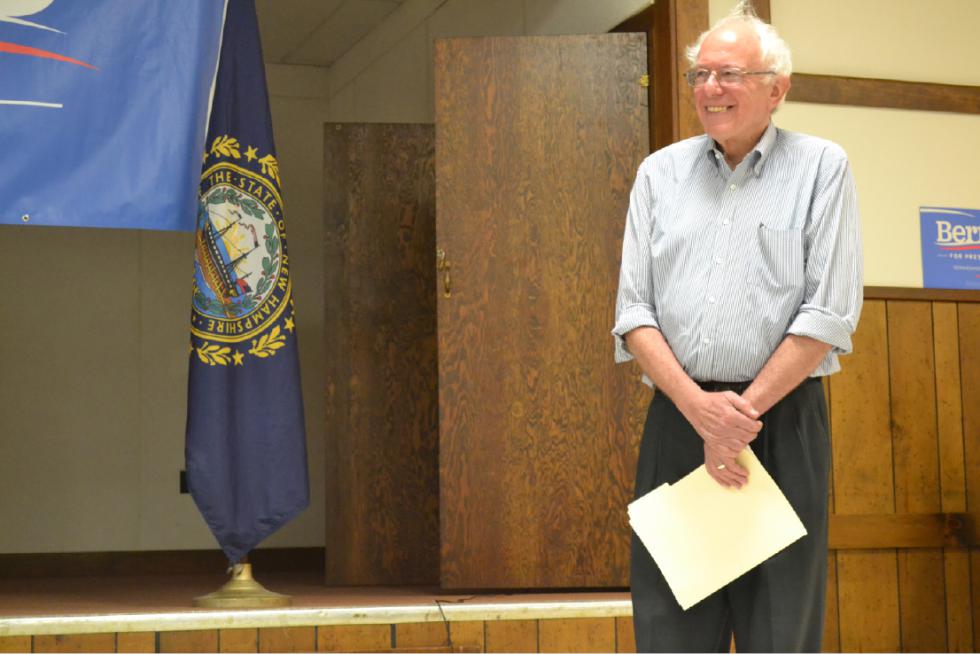

On Sunday, Aug. 2, in the small town of Rollinsford, New Hampshire, Sanders says “Good morning” to a crowd of 300. Then the microphone fails, and static crackles through the meeting room at American Legion Post 47. He looks down at the podium and swipes at the microphone. “Get rid of this,” he mutters, already reaching for a backup mic.

But the first one pops back to life, and Sanders looks up. “Hello?” he echoes. “Okay. That’s a little bit better.” His Brooklyn accent smoothes the roughness in his voice like butter on toast. That’s a little bit bett-ah.

This is the first of three stops today, the most recent in a long string of daily rallies and early morning appearances. Sanders’ white hair is windswept in careless tufts, and his loosely rolled-up sleeves look ready to slide back down. He clutches the podium with both hands and looks up at the eager crowd, frowning thoughtfully.

“All over America, I think people are saying enough is enough,” Sanders begins. “Establishment politics — establishment economics — are not working for the middle class of this country. We need to think a lot more boldly than we have before.”

The hour-long speech that follows touches on many topics in rapid succession. On social issues, Sanders’s progressive stances are familiar. He supports gay rights, access to abortion and contraceptives, and three months of guaranteed paid family and medical leave. He wants to lead comprehensive reforms of the immigration, policing, and prison systems. He calls for efforts to combat climate change.

But mostly, Sanders speaks of a broken America through his preferred lens: economics. He decries the “sad state of affairs” brought about by the 2010 Supreme Court case Citizens United v. FEC, which allowed for the deregulation of campaign spending by organizations — a decision he hopes to overturn through court appointments of his own.

He blasts the financial irresponsibilities of Wall Street, saying that “if a financial institution is too big to fail, it is too big to exist — we have got to break them up!”

By the time Sanders tackles the enormous income inequality in this country, he has shaken off any traces of early-morning calm and quiet. He is fired up.

“There is a billionaire class!” he shouts. “They are enormously powerful. They are enormously greedy. They could care less about anybody in this room, or your kids. They want it all. And what we are telling them is: Sorry! You are not going to get it all!”

The audience applauds loudly. They cheer, too, when Sanders calls for a $15 minimum wage, and for a new trillion-dollar federal jobs program to repair the nation’s infrastructure — providing, by his count, 13 million new decent-paying jobs.

They cheer for his call to move America toward a system of public funding for elections — “allowing people to run for office without having to beg money from the wealthy and the powerful.” They cheer for his call to make all public colleges and universities tuition-free, and to allow students to refinance their student loans at lower rates.

Before a brief question-and-answer period, he seems, finally, to pause for breath.

“We are not a poor country,” he says. “Our job is not to get into the mindset of thinking small. Our job is to think big — to think about what the wealthiest country in the history of the world should look like … Our job is to bring forth a different vision.”

This coming months aren’t just about electing Bernie Sanders, he says. This is about “creating a movement of people prepared to look Washington and the big-money interests in the eye and say: Your days are over. This country belongs to all of us!”

He is loud. He is upset. It earns him a standing ovation.

Ali Webb stands along one wall of the Legion hall, holding her eight-week-old daughter Isabelle. Webb lives in nearby Dover, and this is the first time she has seen Sanders in person.

“I’m ready for a woman president,” she says, “but I think Bernie is more focused on what really needs to change than any of the other candidates. Even if he doesn’t get elected, I hope he changes the conversation.”

We chat about Sanders’ reputation for speaking his mind regardless of his audience. You hear the same message from him whether you support or oppose his agenda. Some candidates have multiple faces. Not Sanders.

Webb ponders whether Sanders’ tone comes off as abrasive. “He’s been doing this a long time,” she says, referring to Sanders’ 16 years in Congress and, before that, his eight-year tenure as mayor of Burlington. “I’d say he’s just frustrated,” she says. “I’m only 30, but I’m starting to get it. If I were him, I’d be frustrated, too.”

Sanders frames that frustration with impressive clarity. The man knows how to lead a room. Sanders has a sturdy and well-practiced hold on his tone and energy level, and he smoothly dials it up and down to avoid fatiguing himself. He is grounded, and that radiates outward.

He also manages to display a vaulting idealism without coming off as naive. His goals are enormous, but they are concrete. If his popularity continues to rise at the current rate, he might well be elected. It is hard to imagine a president who would more profoundly shake up the American status quo.

By the time the Legion hall starts to empty and people step blinking into the sunlight that reflects off the lake across the street, Sanders is already on the road again. His next stop, the town of Franklin, is a 90-minute drive from Rollinsford.

I jump in my car and follow him. The drive is beautiful. I take winding two-lane roads through wooded hills, skirting rivers and ponds, driving fleetingly through tiny centers of towns, down Main Street after Main Street.

Sanders may win here — a place akin to his hometown Vermont — but can he win over the whole country?

Bernie-mentum just might carry him there. In July, he drew a crowd of 4,000 in Kenner, Louisiana. In Dallas, he drew 8,000. In Phoenix: 11,000. And on July 29, a live video rally broadcast to 3,500 meetings around the country drew more than 100,000 supporters.

When I arrive in Franklin, Sanders is stepping from a quiet hallway into the packed gymnasium at the Bessie Rowell Community Center. It is a larger room, with a high ceiling and bright lights, and he ratchets up his energy level for a second trip through today’s talking points. His tone is less intimate this time, more pointed. His gestures are slightly larger. He turns up the heat beneath his words. This is a man who calibrates, naturally, to fill the space he’s in.

It occurs to me, belatedly, that I am going to hear this same speech three times today. Variations are slight, barely noticeable. This is the well-honed gospel of Sanders.

In question and answer sessions throughout the day, Sanders fields queries on all kinds of topics. He responds to a private physician’s concerns by speaking of a need to expand community health centers. When asked how to pay for his more expensive ideas, he speaks of taxing Wall Street speculation and ending tax breaks for large multinational companies.

He assures a concerned Palestinian woman that he supports a two-state solution in the Middle East. He wants better labeling of GMOs on foods, an electrified transportation system, and huge improvements to U.S. commuter rail.

One young man asks how Sanders plans to work with Republicans. After all, they’re not going away anytime soon.

Sanders’ solution is easily stated — and not easy to pull off: Every voter must be vigilant, and hold politicians of all parties accountable to the public interest.

“The way real change always takes place is when people on the bottom begin to stand up,” he says. “This campaign is about building that movement. When we build that movement, we can pass this agenda.”

Even more so at this second town meeting, Sanders seems angry. The word jumps into my head, and I mull it over. Is he angry, really? Surely, as a male politician, he can publicly express his annoyance and displeasure more readily than Clinton, who must constantly confront the sexist stereotype of the hysterical female executive, prone to emotional instability.

But even so, do people see Sanders as a hothead? Does his candor come off as too fringe? How outraged is just outraged enough?

At the third rally — a smaller affair, held in a cozy dining room of The Common Man Inn & Restaurant in the city of Claremont — I ask a few in attendance. No one seems to buy into my skepticism.

Alison Sylvester, a fifth-grade teacher in Springfield, Vermont, has been a lifelong Sanders supporter, and she appreciates his calls for more education and mental health funding. “He gets it,” she says, “and he’s been true to what he says for 30 years. He’s passionate about making life better for average people, and he hasn’t wavered on that.”

I ask her whether she would want to see Sanders dial down the intensity at all if it improved his chances of getting elected. “I don’t think he would, regardless,” she says. “He’s unapologetic for who he is. I think the people who are actually listening to him respect that.”

Christian Spittle feels similarly. “Honestly, I think the fiery tone is what keeps him going,” he says. “It’s what makes him stand out. That’s a good thing.”

Spittle is out on the lawn after the rally, bouncing his 10-month-old daughter Ruby in his arms. Spittle lives in White River Junction, Vermont. He says he is unemployed right now because he and his partner can’t afford childcare. He almost never pays attention to politicians, he says, but “Bernie hit a lot of points home for me. I’ve heard a lot about him, but he blew me away today.”

Dereck Johnson, a health counselor from Plainfield, New Hampshire, admires that he’s never seen a negative campaign ad from Sanders and that Sanders instead relies on “common-sense arguments.”

Music manager Thom Wolke, also from Plainfield, noticed during Sanders’ speech that he almost never looked down at his notes. “You see other candidates up there just reading their speeches off teleprompters,” he says. “But if you believe it, like Bernie, you don’t need to read it. It’s like that old adage: if you don’t tell a lie, you never get lost.”

“And look,” adds Wolke. He pulls off his baseball cap — a Holstein-patterned souvenir from this summer’s Strolling of the Heifers parade in Brattleboro — and shows me where the senator has just signed his name in black marker. “Isn’t that great?”

At a nearby table, volunteers sell hats and T-shirts sporting the words, “Feel the Bern! 2016” in block letters. A selection of pins and buttons offer more cheeky messages: “Hop on the 2016 Bernie Bus,” “Babes for Bernie!” and “Bern Baby Bern!”

But you won’t catch Sanders with any of those pinned to his chest. He draws from the rhetoric of the grassroots outsider, but there is nothing folksy or aw-shucks about him. Sanders is running on a northern brand of populism, fed by town hall discourse, practical arguments, and small-town camaraderie.

Can Sanders’ momentum last into November of 2016? Right now “the Bern” seems to be spreading like a California wildfire.

Whether those flames will be fanned by the national media whirlwind or blown out like a candle may have little to do with Sanders. He’s been touting the same progressive messages for the last few decades, and he’s not showing any signs of backing down from those positions. The prospect of a Sanders presidency comes down to whether America is ready for such a bold, liberal commander in chief.

Gaffes and flip-flops aren’t going to fell Sanders, because he doesn’t play those games. So, if you do catch him kissing a baby on the campaign trail, it may be a sign that something has gone terribly awry with his presidential bid. At this point, though, Sanders has no need to pay lip service.•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.