“Hello” is the key word in two shows running at the Berkshire Theatre Group. One is a musical from the 1950s about a telephone answering service and an outgoing girl (more on that term below) who can turn a subway car full of strangers into a dance party. The other is a world-premiere drama about a lonely woman who can’t even bring herself to greet a neighbor she sees every day on the commuter train.

Walk into Pittsfield’s Colonial Theatre this month and you could be excused for thinking you’ve entered a time warp. Aside from the period décor in the lovingly restored old opera house, the show onstage through this weekend is a lovingly restored throwback, not so much a revival as a recreation of a hit show from the Golden Age of American musicals.

Bells are Ringing opened in 1956 and, the program reminds us, was playing on Broadway at the same time as West Side Story, Candide, My Fair Lady and Carousel. The reason why Bells is less well-remembered than those iconic, game-changing works is at least partly because it’s so resolutely typical of its time, stylistically, thematically and culturally – which could also explain why the 2001 New York revival was a flop.

Ella Peterson is a pretty, playful switchboard operator at the Susanserphone agency, where she’s fallen in love with one of her clients. She knows him only by his voice and phone number, though, and he thinks she is a motherly old lady. He’s a playwright with writer’s block – a perfect candidate for Ella’s vivacious encouragement.

Ella Peterson is a pretty, playful switchboard operator at the Susanserphone agency, where she’s fallen in love with one of her clients. She knows him only by his voice and phone number, though, and he thinks she is a motherly old lady. He’s a playwright with writer’s block – a perfect candidate for Ella’s vivacious encouragement.

The plot is a madcap mixup of disguises, deceptions, coincidences and scams involving crafty bookies, cartoon gangsters and a songwriting dentist. The book and lyrics, by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, feature the witty wordplay that was the team’s specialty, while also epitomizing the period’s insistent perkiness and casual sexism (for example, “I met a girl, a wonderful girl, she’s really got a lot to recommend her, for a girl”). The score is fairly tuneful, and two of the numbers, “The Party’s Over” and “Just in Time,” have become standards. But overall, it’s surprisingly generic, especially considering its creators’ other credits, including Comden and Green’s On the Town and Singin’ in the Rain and composer Jule Styne’s Funny Girl and Gypsy.

But even that is part of the show’s retro charm, which the two leads capably bolster. Kate Baldwin, engaging and dynamic as Ella, can belt with the best, though she lacks the effortless comedic touch of Judy Holliday, who originated the role. Graham Rowat gives the stymied playwright a smooth urbanity and a rotund baritone (Dean Martin played the part in the 1961 movie).

Ethan Heard’s production, choreographed by Parker Esse and ably supported by a hard-working cast in multiple roles, captures the show’s fast-moving feel, as does Reid Thompson’s set-on-wheels backed by a wall of colored light-box squares that recall TV’s Laugh-In – from the sixties, but who’s counting?

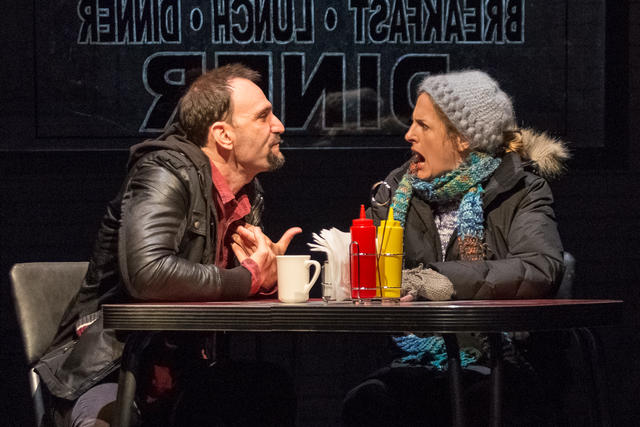

I don’t think Rebecca actually says, “I saw my neighbor on the train and I didn’t even smile,” but that’s the title of Suzanne Heathcote’s play, running through August 15 in BTG’s Unicorn Theatre in Stockbridge. The character does refer several times to her guilt and discomfort at not bringing herself to offer the guy a simple hello, and though it’s peripheral to the plot, it’s central to her dilemma. The play is a metaphor of loneliness, a portrait of people unable or unwilling, in this digital age, to communicate face or face or heart to heart.

Forty-year-old Rebecca is lost in a lonely funk, still deep in mourning for her dog who died over a year ago. Then her teenage niece, Sadie, is dumped on her doorstep after being kicked out of school and more or less abandoned by her parents. She, too, is lost and lonely, acting out in reckless rage and confusion.  Though Rebecca is the central character, the dramatics of the piece really revolve around Sadie, rejected by both parents and now flailing in what’s essentially a foster home with uncaring, or at least careless, guardians. Sadie’s grandmother is a brusque, opinionated old dame with the tact of a six-year-old (but who turns out to be the only one who sees clearly into the fucked-up family dynamics), while her dad is a serial divorcee taking off to Bali on his next marital fling.

Though Rebecca is the central character, the dramatics of the piece really revolve around Sadie, rejected by both parents and now flailing in what’s essentially a foster home with uncaring, or at least careless, guardians. Sadie’s grandmother is a brusque, opinionated old dame with the tact of a six-year-old (but who turns out to be the only one who sees clearly into the fucked-up family dynamics), while her dad is a serial divorcee taking off to Bali on his next marital fling.

Neighbor is a co-production of BTG and the fledgling theatrical collaborative New Neighbor (I think the titular coincidence is coincidental), of which BTG veteran Keira Naughton is a member. She plays Rebecca at the center of a strong cast deftly directed by Jackson Gay.

The problem here isn’t the production, but the play.

Suzanne Heathcote says in the “subscriber enrichment” packet that “My way into a story tends to be through character.” She has, indeed, created a compelling cluster of characters (there’s also a nerdy classmate of Sadie’s and a creepy maybe-love-interest of Rebecca’s) and placed them in a rich dramatic situation. But then she doesn’t convincingly take them anywhere. Repeated failures to communicate culminate in some tentative movement by the three women out of their protective shells, but there’s no real arc that leads there, and the disturbingly ambiguous ending simply happens, as if the playwright was approaching her word limit.

That ending is disturbing because – as was also the case with Legacy at Williamstown this season – I don’t think the playwright realized the implication of her payoff. We see Rebecca emerging from her year-long funk, but the way that transformation is represented indicates, to me anyway, the closing of a circle rather than a way forward, and a bleak outlook for young Sadie. If you catch this show, let me know if you agree.

Photos by Michelle McGrady, courtesy Berkshire Theatre Group

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com