My boyfriend, who is not white, returned home from a shift bartending down the street from our Northampton apartment. Still shaking, he explained he’d just been interrogated by two police officers during his walk home.

They questioned where he had been and what he was doing, and asked him to show them his tattoos. They were looking for someone, they told him.

After a few minutes, the officers were satisfied he wasn’t their guy and sent him on his way.

This happened about a year ago and was his only run-in in Northampton, though throughout our five-plus years together in Western Mass, I can’t count the number of times this has happened. I’ve seen police officers veer up curbs as he walks down the sidewalk in order to have a terse, unfriendly conversation that typically goes like this: Where are you coming from? Where are you going? You fit the description of someone we’re looking for.

It’s these kinds of interactions — ones that leave a wake of uncertainty and mistrust — that Massachusetts lawmakers are pushing to address in bills now being debated at the Statehouse. In the wake of police killings of black suspects and the unrest they stirred nationwide, lawmakers here want to identify biased cops and build public trust.

Some communities in the Pioneer Valley have put themselves ahead of the curve. For the past 15 years, the police departments in Northampton and Amherst have kept track of how frequently officers arrest and write motor vehicle citations for people of different races. The UMass police department also compiles that information, although it’s unclear how long they have.

*Some of the totals do not equal 100 percent due to people who are of more than one race or ethnicity. (Federal policy defines “Hispanic” not as a race, but as an ethnicity.)

In those departments, officials said, the stats show no evidence of systemic racial bias. In recent years, the figures show that the percentage of non-white people arrested or cited by police is generally close to their percentage of the general population.

One exception came last year in Northampton, where black suspects accounted for 9.6 of the total arrests, compared to blacks’ 6 percent share of the general population. Russell Sienkiewicz, who recently retired as Northampton chief, told the Advocate he was initially alarmed by that figure. But then he looked more deeply and learned that some “frequent flyer” subjects accounted for a large share of those arrests, skewing the figure.

“That skews the percentages to make it look high for the year,” said Sienkiewicz. “They were just repeat offenders.”

The Brattleboro Police Department doesn’t compile the information on a regular basis, but was able to gather their data in response to a request from the Advocate.

There, black suspects accounted for nearly 11 percent of arrests in 2013, compared to just over 2 percent of the population. Police Capt. Mark Carignan said that spike was “noted and monitored,” but said officials were reassured when the percentage of arrests dropped to 6 percent last year — a figure he said is the city’s “statistical norm.”

Police officials said that statistics provide a useful tool, raising awareness and prompting important conversations.

“It’s important to just annually evaluate the numbers with regards to demographics,” said Sienkiewicz, who retired June 14. “I’ve chosen over the years to make sure [officers] are held accountable.”

Other large area police forces — Springfield, Holyoke, Greenfield, and Westfield — said they do not regularly analyze such information.

Some police leaders said they see no need to keep data on police encounters with minority residents and visitors.

“I’m thinking: why would we?” said Capt. Michael McCabe of the Westfield Police Department, who said his officers deal mostly with white people. “Our demographics are such that it doesn’t appear to be an issue for us.”

McCabe, also an adjunct professor of criminal justice at Westfield State, says a lot of the attention given to the issue of police showing racial bias is “driven by emotion and not by data.”

McCabe says law enforcement officials are trained to generate profiles of subjects, that it’s part of their job. He instructs me to close my eyes and picture a pedophile.

He asks, “What comes to mind?” I say, a middle-aged white man, a tad overweight, balding. “That’s racial profiling,” McCabe says. “But the facts support that profile.” McCabe says to profile by race, ethnicity, and appearance is sometimes part of the territory.

“Racial profiling is only reprehensible when it’s used to discriminate,” McCabe says.

Springfield officials said they are unable to crunch the numbers due to the volume of police work in the city. That goes for criminal arrests and traffic citations alike. “I don’t even know if our systems could do that,” said Springfield Sergeant Stephen Wyszynski, noting that his department issued about 13,000 motor vehicle citations in 2013 and nearly double that in 2014.

In Greenfield, Deputy Chief Mark Williams said the city department does not analyze demographic data, but has the ability to amass racial information if needed. Greenfield was unable to produce information about arrests, citations, and race before deadline.

David Andrews, 46, of Northampton — who is black — said he hasn’t “experienced any bullshit, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen.” Compared to the police officers in his former home of Chicago, Andrews said Northampton is a paradise. “It’s like hot water to ice,” he said.

Andrews has lived in Northampton for 20 years and said it’s changed in that time. When he first moved here, Andrews said more officers came in contact with him than they do now. Things have gotten better. He recalls a time when a cop pulled up to him and his brother while they were walking by Green Street. Andrews said the officer asked, “Where are you boys going?”

“I would’ve answered him if I’d seen any boys around,” Andrews said. Instead, he just stared at the man with the badge.

Over the years, the black population grew and police behavior improved. “Twenty years ago you could count the black people here on one hand,” he said. “Now, they’re not just running up on people anymore.”

Sienkiewicz said he began compiling demographic statistics for the department about 15 years ago, when racial profiling was employed as a tactic to bust drug traffickers in New Jersey, sparking national debate. During that time, Massachusetts officials discussed ways to ensure officers were held accountable for discriminatory behavior. Though the statewide discussion “fell by the wayside,” Sienkiewicz said, he decided he wanted Northampton to stay ahead of the issue.

Sienkiewicz said that the data collection sets a tone. Supervisors are on the lookout for any patterns of bias and officers know this. “Someone could like to pull more women over,” said Sienkiewicz. “Someone could have an inherent bias. That’s why the data collection is important.”

Sienkiewicz said he’s never seen someone with bias make it through the academy and into the ranks of his department, and he’s happy he has the numbers to back that up.

“I can show clear, unequivocal data that we don’t [show bias],” he said. “It’s not what you look like — it’s what you do.”

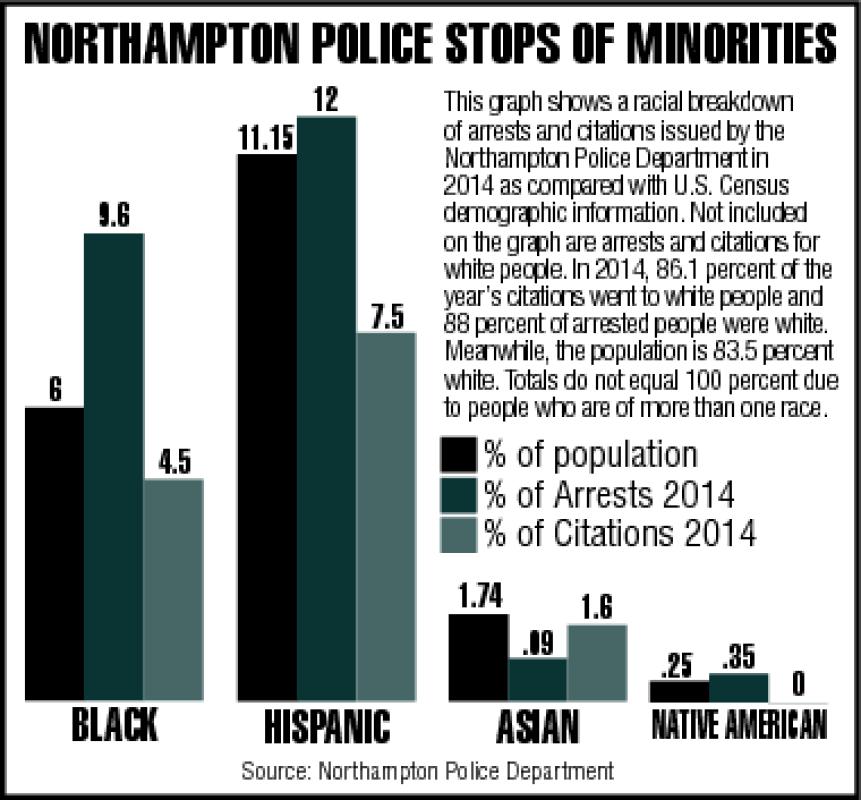

Sienkiewicz said the department compares its racial statistics to the demographics of the greater Springfield metropolitan area, checking to be sure arrest counts fall in line with census-based racial percentages — 83.5 percent white, 6 percent black, 11.15 percent hispanic, 1.74 percent Asian, and 0.25 percent Native American.

He chose those demographics over the Northampton information, which shows notably lower racial diversity, because Northampton is often host to visitors from surrounding towns. The majority of arrests in Northampton, he said — 66 percent — are of people who are not Northampton residents; 19 percent of those arrested in Northampton, he said, identify as homeless or transient.

Of the 5,885 motor vehicle citations issued by Northampton officers in 2014, 86.1 percent of those who got tickets were white, 4.5 were black, 7.5 percent were Hispanic, and 1.6 percent were Asian. Of the 869 arrests made in 2014, 88 percent of the subjects were white, 9.6 percent were black, 12 percent were Hispanic, 0.9 percent were Asian, and 0.35 percent were Native American.

Northampton’s new police chief might find her predecessor’s statistics useful. At a public meet-and-greet during the vetting process for the job, Jody Kasper fielded questions from some residents who said they felt people of color are unfairly targeted in Northampton. Kasper, a veteran of the force who most recently served as second-in-command, was surprised to hear it.

“We’re well aware of the national conversation, of a lot of groups feeling a rift with police and not feeling understood, but this is the first time I’ve heard that about Northampton,” said Kasper. “But of course, if people have concerns, we need to hear that. We need to address that — that’s not good.”

Residents of Northampton’s Hampshire Heights said the neighborhood is no stranger to visits from the police.

“I don’t think you’re going to get much positive response from the people in here,” said Andrews, as I take a stroll through the neighborhood asking for thoughts on NPD.

Do the police come through here a lot? Andrews looks at his watch in response. “Is it 8 o’clock yet?” His girlfriend, Toni Dolan, 33, who lives next door, said her children are scared of the police. She said officers are often responding to calls, but also frequently prowl the neighborhood for signs of trouble. Dolan said she understands they have a job to do, but the neighborhood of lower income residents struggles enough.

“No one’s here because they want to be,” she said.

Dolan said she fled her abusive husband about five years ago and public housing is all she could afford on her own. Dolan’s daughter, Kiara Badillo, 16, heard us talking and came outside to join in. Badillo said looking out her window night after night and seeing police cruisers is oppressive.

“To them everyone is the aggressor,” she said. “They make me feel uncomfortable. I’m more scared of them than I am walking down the street in Springfield.”

David’s son, Djon, 22, walked up to the apartment and heard us talking about the police. “I hate them,” he said. He said he was recently riding his bike through town and rode up onto the sidewalk for a stretch. An officer saw him and made him walk his bike rather than ride it, while he said a white man behind him on a bike went unstopped.

Another Hampshire Heights resident, Margaret Martin, 56, said there’s tension between neighborhood residents and police officers. But she said that’s because some of the residents are “criminally active” and the rest don’t like to talk to the police officers about it for fear of retaliation.

“I’ve seen a lot, but now I’ve learned to keep my mouth shut,” said Martin. “And it makes their job harder, the police.”

“I haven’t had any complaints and I’ve lived here all my life,” said Luis Rivera, 25, of Northampton, while walking to his car in Hampshire Heights. “I’m kind of glad I live in Northampton, because cops everywhere else are starting to act up.” Others say seeing officers in the neighborhood so frequently sends a negative message, especially for the many children growing up in that environment.

“We do routinely drive through lots of places,” Kasper said. “Some people like to see an officer drive through their neighborhood because it offers a sense of safety.”

Fatima Salaam, 53, of Northampton, said she hasn’t trusted the police since an officer allegedly shot and killed her father in Brooklyn, New York, in 1989 for selling loose incense on the street. So she wasn’t surprised when Northampton Police officers detained her last year when a fellow shopper at CVS said Salaam had called in a bomb threat to the store. She said the woman only accused her because she was wearing a traditional Muslim head scarf.

“I don’t trust them,” Salaam said of police.

Though she doesn’t recall this specific incident, Kasper said, it’s considered good practice to detain someone accused of something dangerous so they don’t go running off while officers get to the bottom of it.

Kasper said every police officer in the state receives four hours of diversity training at the academy, though fair and impartial policing methods are woven throughout the academy program. This diversity training, along with the department’s anti-discrimination policy, is reviewed on an annual basis, she said.

Additionally, several members of the department have taken an elective 32-hour course dedicated to equipping officers to safely get help for those with mental health issues.

Kasper said she’d like to supplement existing training with a cultural awareness course, but unfortunately, she was surprised to find, they’re not easy to track down.

“It’s hard to find, but certainly I think it’s valuable,” she said. “I think that with everything that’s gone on in the past year we’ll probably see an uptick in those types of courses,” adding that she’ll be watching for those that do crop up. “When I first came on I remember a lot more diversity training,” she said, recalling how racial profiling was a burgeoning issue when she joined the city department in 1998.

Down the road in Springfield, Sgt. John Delaney said there’s no need to compile racial data. “There’s no red flags in our department in regards to things of that nature. We get along very well in the community — with all races and genders.”

Some people in the Springfield neighborhood known as “The X” have a different perspective.

Ishmael Peña, 26, said he was shocked by the way Springfield Police officers arrested his friend on June 8.

“They roughed up my boy,” Peña said. He said that he understands why they arrested his friend, who is not white, but he wishes he had a camera out to document the way they did it. “They had no reason to do that. They nearly ran him over. Maybe that’s just how it is out here in Bangfield.”

Delaney says officers arrested Peña’s friend, Ishmael Ramos, because they caught him selling heroin on Worthington Street. He says Ramos already had an existing warrant out for heroin distribution. Reports from the night show no record of a fight between Ramos and the officers.

“I don’t know what this person saw,” said Sgt. Delaney. “[Ramos] wasn’t picked on because of his race, he was picked on for selling heroin. And the second time at that.”

Delaney says he’s not surprised to hear some shared a different opinion of police — they have a tough job that too often involves taking away someone’s freedom.

“If some officer is having a bad day then that person’s perspective of police officers is not good, but overall police officers are caring individuals,” Delaney says. “Are there bad police officers? Yeah, just like there’s bad reporters — we hire from the human race just like everybody else does. But 99 percent of us do a really good job serving the public.”

Capt. Michael McCabe of the Westfield Police Department says that Westfield has so few people of color that racial data collection doesn’t make sense for the department.

When the question of racial bias surfaces, McCabe said it’s a tricky subject to navigate, especially when people who have done wrong don’t want to admit it.

“Nobody really wants to come out and have that conversation,” said McCabe. “It’s easier to blame law enforcement for what appears to be racial bias against a certain demographic.” He said the tension between officers and black people is such that black subjects are instantly on the defensive.

“It’s an interesting demographic that you can’t really have a conversation about,” said McCabe. “As sure as I am sitting here, 100 percent of times I’ve stopped a person of African-American descent, their way of thinking was that the reason I was stopping them was because of the color of their skin. That’s a cultural issue.”

When it comes to motor vehicle stops, McCabe said radar guns don’t discriminate. “I don’t know if they’re black, white or purple when I’m pulling them over.”

While analyzing arrest and traffic citation records for racial bias is illuminating, it doesn’t tell a complete story.

Tracking motor vehicle searches by race can often be more revealing, said Jack McDevitt, director of Northeastern’s Institute on Race and Justice.

“Police will often tell you that frequently they don’t know the race of the person they’re pulling over,” McDevitt said. “But once you’ve pulled someone over you know what their race is” — and at that point, officers make choices about whether to conduct a search.•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com

The Law

Currently, state law requires police departments to note a subject’s race on records of arrests and motor vehicle citations. However, there is not currently a requirement for police to document the race of people involved in motor vehicle stops that do not result in a warning or citation, or in searches and interactions on the street.

Two state bills proposed by Second Suffolk District State Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz would change that by requiring officers to document race in their less formal interactions with citizens. The bills are still in the preliminary legislative phases.

“It’s an issue that we’ve long been hearing about from our constituents,” said Chang-Diaz, who said that people of color often feel targeted by police officers. “I think the core philosophy is you can’t manage what you don’t measure. The data probably will reflect that in many parts of the state police are doing great work, that they’ve made great improvements, and we also want to be able to see where there are problems.”

Lorie Fridell, CEO of Fair and Impartial Policing — a Florida based organization that travels the country to train police departments in the art of recognizing bias — said her organization is increasingly in demand. She said the organization, partially funded through the Department of Justice, is expanding since President Obama’s task force on 21st-century policing recommended more departments seek training.

Fridell said the training program includes education on implicit bias. Explicit bias is often what comes to mind when someone brings up the topic of bias — the kind of bias evidenced outright and consciously acknowledged.

Implicit bias is much more common, she said, and it “can happen outside of conscious awareness.” Fridell said legislators should set aside issues of data collection and instead spend time and energy on funding training, leadership, outreach. She said implicit bias is a pervasive issue that data collection alone can’t fix.

“If you hire humans to do policing you have to be proactive,” said Fridell. “There’s no department that doesn’t have work to do on this issue.”•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com