Last week, Superman stopped by Crocker Farm Elementary School in Amherst. He crashed library hours, where the kids had gathered for a special screening of short films they had made in school. The costume fooled no one — turns out it was special education teacher Alvie Borrell. But how often do you receive a film award from a superhero?

“The kids love to see their teachers being goofy, and they love seeing themselves as the stars,” said fifth grade teacher Alice Goodwin-Brown. “We’ve had to let so much of that go.”

Goodwin-Brown has taught at Crocker Farm for 26 years. Each year, she said, the school has had less time to plan teacher-devised creative events like this one, and it is a direct result of the hours needed to prepare students for standardized testing.

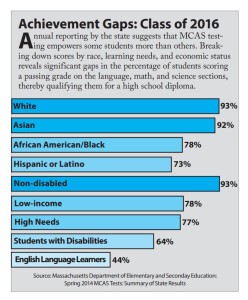

Click on image to enlarge.

When Goodwin-Brown took this teaching job in 1989 — four years before the development of the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) — Crocker Farm staff asked her to submit an essay describing her philosophy of education. She wrote that, above all, a teacher teaches what they know about the world.

“You bring your love of the world to your students, and the art of teaching is figuring out how you’re going to get that across,” she said. “We’ve done a 180-degree flip since then. We have an almost entirely scripted curriculum.”

Goodwin-Brown is not alone in her frustration. On June 11, hundreds of parents, teachers, and supporters — many of them called to action by the Massachusetts Teachers Association — pulled their own Superman move, crashing a meeting of the Joint Committee on Education in Boston. Lawmakers were there to discuss House Bill 340, which would remove the requirement that students pass the MCAS in order to graduate. The bill also calls for a three-year moratorium on the implementation of the new PARCC exam, funded by President Obama’s Race to the Top initiative in 2010, which adheres to national Common Core curriculum standards. Gov. Baker is set to decide later this year whether the PARCC test, which is administered twice yearly rather than once, will replace the MCAS statewide.

In a letter sent by the Amherst-Pelham Regional School Committee to state legislators in early June, committee member Katherine Appy pointed to studies suggesting that high-stakes testing only measures a small range of skills that emphasize good test-taking over comprehensive learning.

But that does not mean that standardized testing, by definition, misses the mark.

Stephen Sireci, the director of the Center for Educational Assessment at UMass Amherst, teaches a course on test construction. He said he is eager for a larger discussion of what works and what doesn’t when it comes to standardized tests. But he does not support the moratorium proposed by the teachers union, of which he is a member.

“We need the information that these tests provide,” he said. “The problem is that tests don’t measure everything students and teachers do. The idea that we should be evaluating teachers based on their students’ test performances is really not a good idea.”

Building a new standardized test from the ground up would take enormous time and effort, Sireci said. But if Massachusetts ends up at that crossroads, test creators will need to start by defining a reasonable amount of time in which to test kids during the school year. “Is it five days? Ok, then let’s develop a system around that. It will look very different than a test held over three days, or 10 days.”

Tests should also vary based on purpose, he said. For example, a test that measures how much a student knows at the end of a year should be written differently than one measuring the rate of improvement over the course of that year.

The answer, Sireci added, may come in the form of tests that are more individualized and flexible. Computer-based tests have the capacity to adapt content and difficulty moment-to-moment based on student responses, much as harder levels in a video game become playable only as easier levels are completed.

“That’s the future of testing,” he said. “The idea that a standardized test should level the playing field — same content for everyone, and all scored the same way — is laudable. But when it’s not for everybody, it doesn’t work.”

Meanwhile, criticism of the current standardized testing is widespread. A 2013 paper from Stanford University’s Center for Education Policy Analysis concluded that the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 — President George W. Bush’s stab at closing racial and socio-economic achievement gaps — had effectively done neither. And tempers have flared throughout the country this spring.

In Albuquerque, New Mexico in March, hundreds of students walked out of Rio Grande High School and marched to protest the PARCC test. In April, several districts in New York’s Lower Hudson Valley reported that at least 25 percent of students opted out of taking the state’s standardized test. So did 100 percent of the junior class at Nathan Hale High School in Seattle that same month.

In large part, students, parents, teachers, and school administrators are protesting the ways in which the high-pressure culture of standardized testing is changing the climate of the school day, dictating curriculums, and stressing out test-takers.

It doesn’t help that the British-owned corporation Pearson Education — which won the bid to deliver the PARCC test, and which stands to earn over $1 billion in the coming decade if enough states adopt the test — keeps getting into hot water. The company, which has an office in Hadley, drew criticism in Texas in 2013, where it was recruiting test scorers from Craigslist. The year before, New York students found more than two dozen errors in their Pearson-developed state test. Among those, a question about a talking pineapple in a foot race was deemed so absurd that it was promptly removed.

Even discounting such errors, the culture of standardized testing is warping school policies and priorities, Goodwin-Brown said. “Studying anything in-depth is less and less possible,” she said, and added that the staff at Crocker Farm has been compelled to reduce the number of class meetings, discussion periods, and programs for reading buddies and volunteer work around the school.

Talent shows, which used to be held every other month, no longer happen, she said, because teachers do not have the free time to plan them. “That felt like a real loss,” she said. “Those events allow for kids who don’t have as much academic success to still feel that they have a place in the school.”

Goodwin-Brown is not averse to testing. Neither is the Massachusetts Teachers Association. In their resolution calling for a moratorium, the union supports “locally developed, authentic assessments,” created by “educators, parents, and other members of our communities” working together.

“We just really need to limit what we’re testing to what is developmentally appropriate,” Goodwin-Brown said. “Instead of letting them explore their thoughts and learn to be articulate on paper, we’re teaching them to write short answers to open response questions and how to deal with multiple choice. That’s it.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com