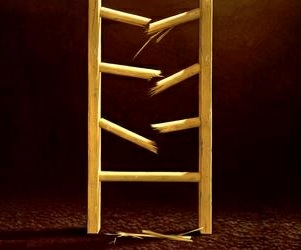

T he American Dream is a fitful one these days, marked by rising income inequality and a decade of middling economic growth. But a national study published this month by the Equality of Opportunity Project at Harvard University suggests that children from poor families living in certain cities and towns stand a better chance of escaping poverty than others.

Let’s look specifically at children from families belonging to the lowest income group, the 25th percentile, where nationwide the average household income is about $30,000 a year.

Broken down by county in Massachusetts, the data from the study show clear regional differences in the ability of these children to gain upward mobility later in life. Children in poor families living in Franklin and Hampshire counties, for example, grow up to make about $1,100 more per year than the national average by the time they’re 26.

In fact, the study found that the younger children are when they move to Hampshire and Franklin counties, the less likely they are to become single parents, and the more likely they are to go to college and earn more money.

Hampden County didn’t fare as well. Poor children who spend the first 20 years of life there make $830 dollars less per year than they would if they were living in a county with an average level of income mobility.

In Berkshire County, the picture is better, but not great: poor children living there end up making $470 less per year than the national average.

This study, conducted by Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, tracked the earnings records of more than 5 million poor families with children who moved from one area to another across the nation in the 1980s and 1990s. Their findings suggest that moving children to new areas relates causally to how well they do later in life — which means, in effect, that they have mapped the best and worst places to grow up in America.

Is it true that poor children in Hampden and Berkshire counties are worse off? We asked several nonprofits and human services groups in those counties whether these findings make sense.

But the answer to that question is not a simple yes or no. Like throwing a rock into a pond, our initial question rippled out into a larger conversation on the complex routes into — and out of — generational poverty.

In Berkshire County, poverty is rural, said Deborah Leonczyk, the director of the Berkshire Community Action Council in Pittsfield. In the Berkshires, she said, the most pressing obstacle to financial stability is transportation, mainly the lack of jobs available to residents, young or old, who do not own a car.

“We have 18 towns that aren’t served by public transportation,” said Leonczyk, “which makes it difficult for most low-income rural folks to actually find employment.” Even after a worker is hired, she added, commuting without a car is often untenable.

If a worker in Sandisfield — a town without public bus service — is offered a job at the Berkshire Mall in Lanesboro, for example, the only way to get to work is by taxi — which costs $91 each way.

Lack of public transit affects access to much more, of course, including daycare options, grocery stores, and the unemployment office. And even in areas with public transportation, limited night-time operating hours preclude commuting to third-shift jobs — which are the entry-level and low-wage positions that impoverished workers are most commonly hired.

That’s why Leonczyk is seeking state funding for a new affordable public transportation plan, which will test pilot commuting routes for low-income workers over the next three years. Leonczyk suspects that employers will pay to fund a low-cost shuttle once they see a decrease in turnover and an increase in productivity. “I think it’s a no-brainer,” she said.

And this Harvard study? The findings make perfect sense, said Leonczyk. “I think the study is very true. When parents are stuck in poverty, children have less opportunity. The first thing is to make sure that families can keep as much discretionary income in the home as possible.”

Robin Hodgkinson, the director of the Community Education Project in Holyoke, faces challenges distinct to Hampden County’s more urban landscape. He said that the results of the Harvard study should be read with an awareness of racial and language barriers in places like Holyoke where 47 percent of the population is Hispanic.

“If children are expected to speak mainly English at school, and they speak Spanish when they go home, typically they are lagging by the third grade, not reading at grade-level,” he said. “They never catch up after that. So you end up with a population of young adults who want to enter the workforce but have limited English proficiency, which makes it difficult for them to get professional-level jobs.”

The Holyoke public school district went into receivership on April 28, requiring the state education commissioner to step in and oversee systemic improvements. Among other things, this will result in an extensive rehiring process for teachers. Hodgkinson hopes such change paves the way for more bilingual classrooms, led by teachers who are fully proficient in both English and Spanish.

And if Holyoke can increase its graduation rate — which, at 60 percent, was the lowest in the state in 2014 — more young people will carry the high school diplomas and GEDs necessary to apply for vocational jobs and training programs.

“It used to be that a high school diploma qualified you for a reasonably well-paying industrial job,” said Hodgkinson. “But times have changed. Now people need some sort of post-secondary education. Without that, you’re doomed to a low-paying job.”

Joan Kagan, president of the early-childhood education nonprofit Square One in Springfield, agreed that raising wages for poor young people requires a whole-family approach. “The way to help children is to make sure their parents do well also,” she said. “It has to be holistic.”

Nearly 98 percent of Hampden County residents that come into Square One live at or below the poverty level, Kagan said. But their challenges go beyond the economic. The more resources put toward protecting a child’s cognitive development and emotional health early on, the better the groundwork for academic achievement and professional success down the road.

“If they’re hungry, they’re not learning,” she said. “If they’re not sleeping because of disturbances at home, they’re not learning. Higher rates of crime, substance abuse, incarceration … all of these things impact a child’s outcome.”

This is why looking at poverty rates based on geographically can only reveal so much, said John Roberson, the vice president of children and youth services at Springfield’s Center for Human Development. Roberson said the center works mostly with impoverished families, matching them with employment, mentoring, and behavioral health services throughout the western part of the state.

“I work with youth from rural areas and from the inner city,” he said. “And poverty is everywhere. Families face challenges no matter where they come from.”

Although Roberson found the data from the Harvard study interesting, he said that there is no area of the country that does not need more skill development and better-paying jobs for these tight times.

“Young people face their own challenges, but poverty is generational,” he said. “We need to do whatever we can to break that cycle.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.