If you’re an avid theatergoer – and if you’re not, what are you doing here? – I urge you, if and when you’re next in London, to take the backstage tour at the National Theatre.

After many visits to the National over the years, last month I got around to doing just that, as well as catching two shows there (see below). The tour is an hour-long investigation of the vast South Bank facility, in which you not only look into the company’s three theaters but thread the building’s backstage labyrinth to poke around costume and scene shops, visit rehearsal rooms and venture behind the scenes of one of the main stages – the exact itinerary and extent of access determined by what’s going on at the time in these always-busy venues.

Wearing day-glo orange safety vests because we’d be entering areas normally off limits (our personable young guide told us that some groups are issued hard hats), we strolled through temporarily unoccupied rehearsal halls with set plans taped to the floor and stage managers’ paraphernalia scattered over tabletops; said hello to a scene-shop team stapling fabric onto flats for the upcoming production of Everyman; and perched in the balcony of the Olivier Theatre overlooking the bowl of the auditorium and the massive thrust stage.

Fascinating facts: The 1,100-seat Olivier, named for the National’s first artistic director and preeminent actor of his age, is modeled on the ancient Greek amphitheater at Epidaurus. The steep semicircle of seats, all of them affording a good view and a surprising sense of intimacy, describe a 118° arc. Why? Because that’s the range of a person’s peripheral vision, so that an actor standing stage center can see the whole house at once. The seats are upholstered in purple. Why? Because that was Olivier’s favorite color.

We then descended through winding hallways and a couple of heavy fire doors to find ourselves in the Olivier’s backstage. Two shows usually run concurrently in the theater, the sets for one stored behind, above or below the stage while the other is being performed. The off-show this day was Treasure Island, the theater’s current “family spectacle” in the tradition of War Horse. We passed the Admiral Benbow Inn’s façade and the huge ribs of the Hispaniola’s hull, and gazed up into the vanishing heights of the fly tower, from which whole sets can be lowered onto the stage.

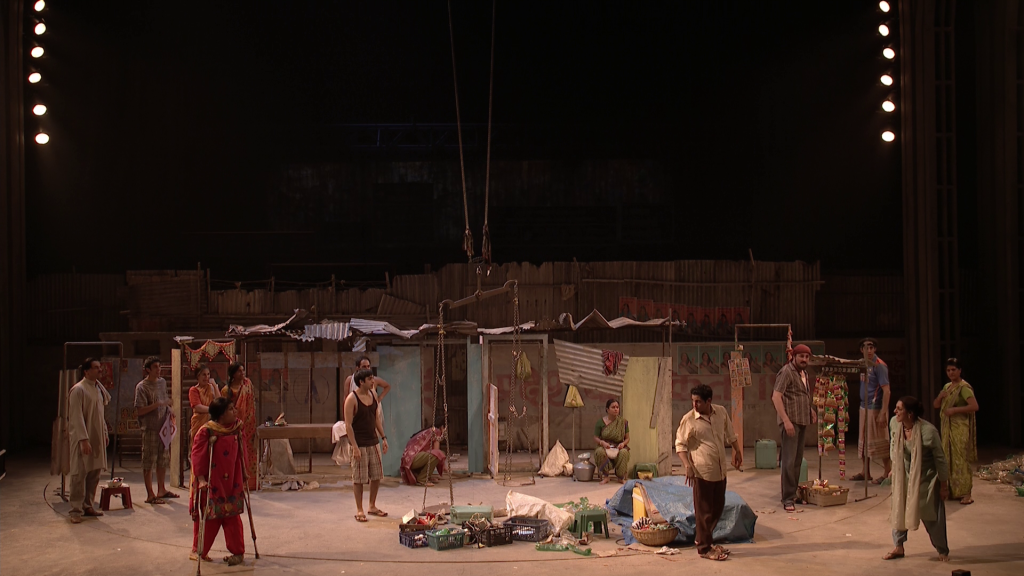

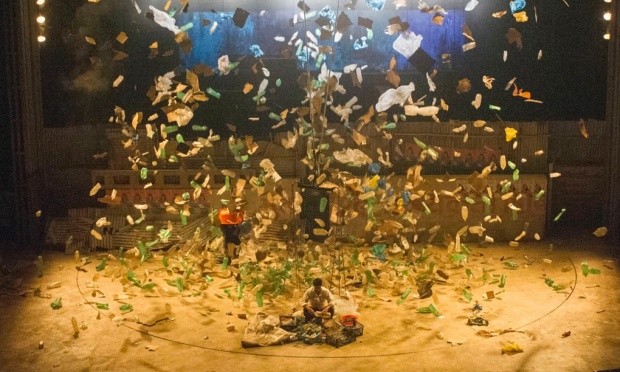

Then, suddenly, we emerged onto the stage itself: a broad half-disc, backed now by a corrugated-iron wall lined with posters promising “Beautiful Forever Beautiful Forever” and strewn with trash – the set, as it happens, of the play we had seen there the night before.

Behind the Beautiful Forevers is based on the bombshell nonfiction book by Katherine Boo, who spent three years in Annawadi, a slum-city whose residents live by recycling the rubbish generated by the posh hotels that ring Mumbai airport, along with other marginal schemes to keep society’s underbelly fed. The book was dramatized by David Hare, whose politics give the piece a sometimes Brechtian feel: “How do people get on?” one character asks rhetorically, in that lilting cadence of the subcontinent. “They use what they have learned from the rich people: If you don’t think it’s wrong, it isn’t.”

Under the direction of Rufus Norris, the National’s new artistic director, the large, all-Asian cast (the theater’s first) fill the stage with noise and movement, creating a self-contained, almost Dickensian underworld where corruption is a law of nature and relationships are built on trusting no one. There are also, thanks to the Olivier’s impressive technical capacity, a couple of eye-popping visual effects: The shadow of a huge jetliner roars over the slum – and the heads of the audience – followed by an avalanche of trash that covers the stage and is speedily gathered up by scurrying “pickers” and “sorters.” In the sprawling narrative, where humor and hope battle gamely with loss and despair, we meet thieves and idlers, bent cops and cynical judges, young people with lofty ideals and hopeless dreams, and at the center of the interweaving plotlines, three extraordinary women.

Zehrunisa (played by the actor/writer/activist Meera Syal) is proud, ambitious and foul-mouthed, a Muslim among Hindus and a successful businesswoman in a hand-to-mouth economy. Asha (Stephanie Street) is the self-styled “go-to woman,” part loan shark, part neighborhood fixer for trouble with the authorities. And there’s volatile, promiscuous, clubfooted Fatima (Thusitha Jayasundera), whose resentment of Zehrunisa’s prosperous family leads her to a disastrous act of vengeance – a contrast with the dogged optimism and cooperative spirit that keep most of the other characters coping, barely but bravely, behind the impregnable walls of wealth and power.

From the spacious Olivier, we were led through more back corridors and down secret stairways to the National’s smallest theater, the newly refurbished and renamed Dorfman. Formerly the Cottesloe, this intimate black box seats the audience around a rectangular platform almost within touching distance of the actors. The set we inspected was for a new play, Sam Holcroft’s Rules for Living, a dark comedy that depicts domestic life as a game show, complete with scoreboards on the kitchen walls. Rules is currently sharing the space with Tom Stoppard’s latest, The Hard Problem, about the nature of consciousness at the mysterious intersection of psychology and biology.

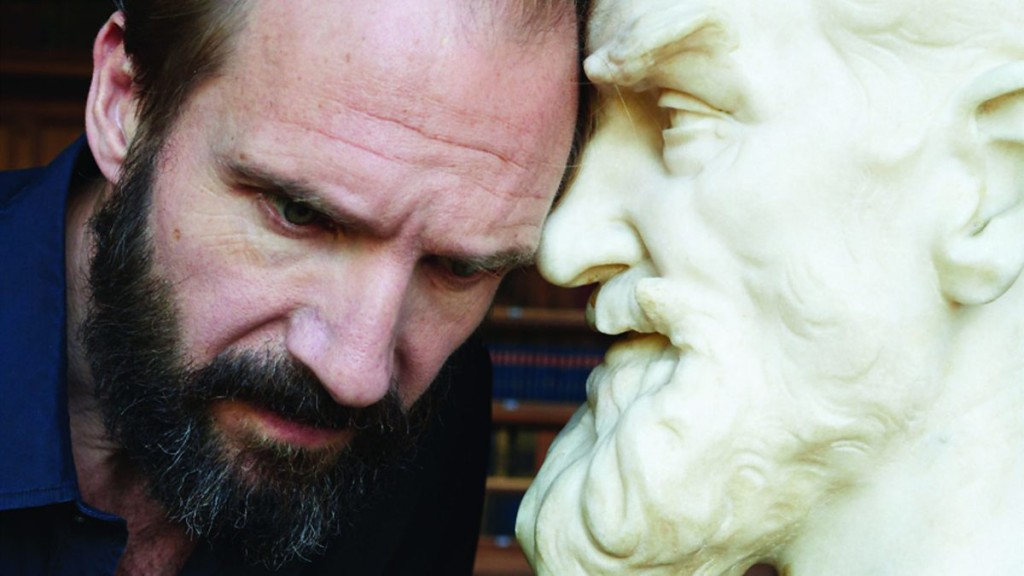

From the Dorfman, we moved on to the auditorium of the Littleton Theatre, whose 890 seats and proscenium-arch stage make it the National’s most conventional venue. We watched stagehands in hard hats guiding a set piece into place as it descended from the flies: one oak-paneled wall of a Victorian-era study, its high double doors flanked by well-stocked bookshelves. (Our guide shared a trade secret: They’re all real books, but with the innards cut out and replaced with Styrofoam to ease the weight on the fly mechanism.) That period façade, though, was surrounded by a towering white wall of translucent Plexiglas – the set for the theater’s current blockbuster hit, George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, starring Ralph Fiennes.

Which, as it happens, was the very show we were going to right after the tour.

Man and Superman is one of the most mischievous, mercurial, rhetorical and, in its time, subversive of Shaw’s philosophical comedies. First performed in 1905, it has a temperamental, opinionated, gleefully contrarian hero, Jack Tanner – a virtual self-portrait of the playwright – whose greatest joy is discomfiting the comfortable and whose patrician-socialist views are set out in his Revolutionist’s Handbook (which is actually included in the published edition of the play). There’s also a self-sufficient, insubordinate heroine, Ann Whitefield, who pulls the hero’s strings like a puppeteer; a gang of leftist Spanish highwaymen (and women) who pass the time between holdups arguing political philosophy; an act-length dream sequence set in a particularly urbane version of Hell; and an iconoclastic point of view that’s pro-feminist, anti-establishment and irreligious.

Indeed, as his biographer points out in a program note, in this play Shaw turned nearly all the dramatic and social conventions of his age “inside out and upside down.” An inverted take on the Don Juan saga (with a cast that parallels Don Giovanni) in which the man is not the predator but the prey, it’s an unromantic romantic comedy full of “paradoxical reversals,” making it “a surprisingly modern play.”

And that’s where the hybrid set we saw on the tour comes in. Contrasting, indeed contradicting that old-world library, Jack appears in jeans and a sport jacket, his motor car is a late-model Jaguar, and he receives a letter in the form of a text message.

Man and Superman was indeed radical and modern in 1905. But in Simon Godwin’s production the updated surroundings don’t really match the script. Two examples: In Act One, everyone (except Jack) is scandalized at the news that a young unmarried woman is pregnant, and even Jack’s so-what response is an argument instead of a shrug. And when a young American shows up in Act Two, his Edwardian locutions (“I should like to suggest an extension of the traveling party to Nice, if I may”) don’t match his crewcut accent.

I guess the contemporary overlay is intended to underscore the play’s timeless themes, the way modern-dress Shakespeare is supposed to. Except this play’s themes aren’t really timeless. Its “New Woman” feminism, utopian socialism and social Darwinism belong to the period, not the ages, so the tension between text and context tends to work against the play instead of illuminating it.

That said, the production crackles with energy and humor, and even though it’s the talkiest play on either side of the Atlantic right now (and three-and-a-half hours long) its rapid-fire dialogue is made consistently funny and engaging by lively performances. Fiennes gives Jack Tanner a manic, explosive momentum that fills the stage without dimming the light on his supporting cast. Of these, I particularly admired Indira Varma, smart and feisty as Ann, and Tim McMullen, dry and droll as the gentlemanly chair of the brigands’ discussion group, then dapper and debonair as the Devil (yes, the Don Juan in Hell sequence is included here).

You’ll have to be in London to do the National Theatre tour, but you needn’t be to see Man and Superman, or Stoppard’s The Hard Problem, for that matter. They’re both coming shortly to the Amherst Cinema in its NT Live series of high-definition live-to-screen broadcasts, along with another David Hare play, the earlier, quieter Skylight. See amherstcinema.org for information and schedules.

Photos courtesy of the Royal National Theatre

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com