When Adam Cohen contributed $500 to Michael Bardsley’s mayoral campaign in Northampton, he said he wasn’t expecting anything in return. Neither was his wife, Jendi Reiter, when she donated $500 to the campaign, he says.

Cohen, a blogger and leader of the North Street Neighborhood Association, says he doesn’t often give so generously to politicians, but he felt strongly Bardsley would be good for Northampton and wanted to support him to the maximum extent possible, adding that he and his wife are fortunate enough to be able to do so.

“I thought he was an important independent voice for Northampton and I wanted to show my support,” Cohen says of Bardsley. “I wanted to give him as much help as I could.

“I’m not too concerned someone would have undue influence” over $1,000, Cohen says.

Let’s hope so.

Joining in the national trend of dismantling campaign finance controls, in January the maximum donation a person can make to a Massachusetts candidate in a local election went up from $500 to $1,000.

In 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court Citizens United ruling dismantled existing limits on campaign spending by corporations and unions. Then, last April, the court axed longtime caps on the total an individual can contribute to federal candidates within an election cycle.

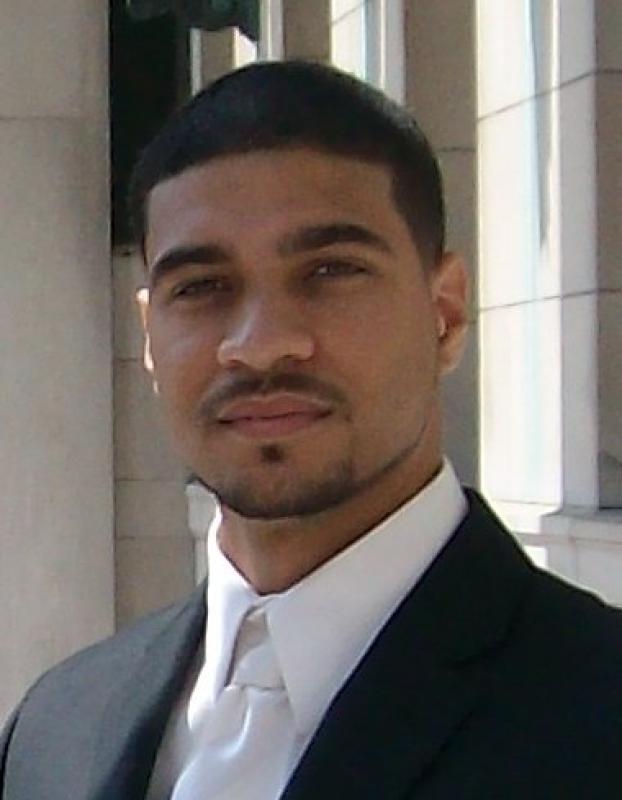

Not much has been done nationwide to stem the tide. Locally, however, Northampton City Councilor Ryan O’Donnell is trying to pass an ordinance that would roll back the effects of the new state maximum contribution for elections in his city. He wants the maximum per-person donation in city elections to stay where it was: $500.

O’Donnell says the ordinance is more of a statement against the deluge of unrestrained cash in politics than anything designed to have a big local impact. There aren’t a lot of political donations around here that make it to $500, according to Advocate research of Springfield, Greenfield and Northampton local campaign finance records from 2012 to 2014.

During those years there were thirtyeight $500 donations to Springfield candidates, nine in Northampton, and two in Greenfield.

Councilor At-Large Jesse Adams says he can get behind the sentiment in the proposed ordinance, but as maximum contributions are uncommon in Northampton and the ordinance could prove difficult to enforce, he’s skeptical such a change would actually accomplish much.

“It seems like it may be more of a statement than anything,” Adams says. “I don’t necessarily oppose it, I just don’t know if it will do anything.”

Talking money

Many elected officials in the Valley, along with the people who donate significant amounts to their campaigns, say they’re in favor of campaign finance reform and donation caps.

“It does seem to be getting out of hand nationally so I wouldn’t be surprised if the city council’s efforts are a repudiation of what’s happening there,” says Pat Goggins, owner of Goggins Real Estate in Northampton.

Goggins contributed $500 in December 2012 to David Narkewicz’s mayoral campaign. As a longtime friend to Narkewicz and as someone who worked on his campaign, Goggins says it felt natural to give as much as he could. He says money’s influence in politics may not be a problem in Northampton, but that councilors’ attempts to untangle cash from campaigns likely stems from the financial sway observed in state and federal races.

Sally Markey says she and her husband gave the maximum donation to Springfield City Councilor Tim Allen’s 2014 campaign for state senate. She says the money would help Allen fight back against donors with deep pockets backing his opponent — and winner of the election — Eric Lesser. Markey says the loss had more to do with Lesser’s connections with “outside money” than with substance.

“He’s very much a man of his word; he’s very invested in the community,” Markey says of Allen. “We gave more to Tim than most people because we felt it was important. I think there should be caps and everyone in the race should abide by the same rules — in order for it to be a democracy you have to have a level playing field.”

Some donors say they should be able to do whatever they like with their money and that includes donating however much they see fit to candidates. Peter Picknelly, CEO of Peter Pan Bus Lines, gave $500 to Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno’s campaign. He says he regularly contributes to political campaigns in the area and that he decides how much by the candidate’s track record of boosting the city and the economy.

“I support politicians who I think do a good job of supporting our city.” As for dollar amounts: “I take it on an individual basis — I base it off of how well they’re doing at improving our city and our economy. And the [$1,000] cap would allow me to give more.”

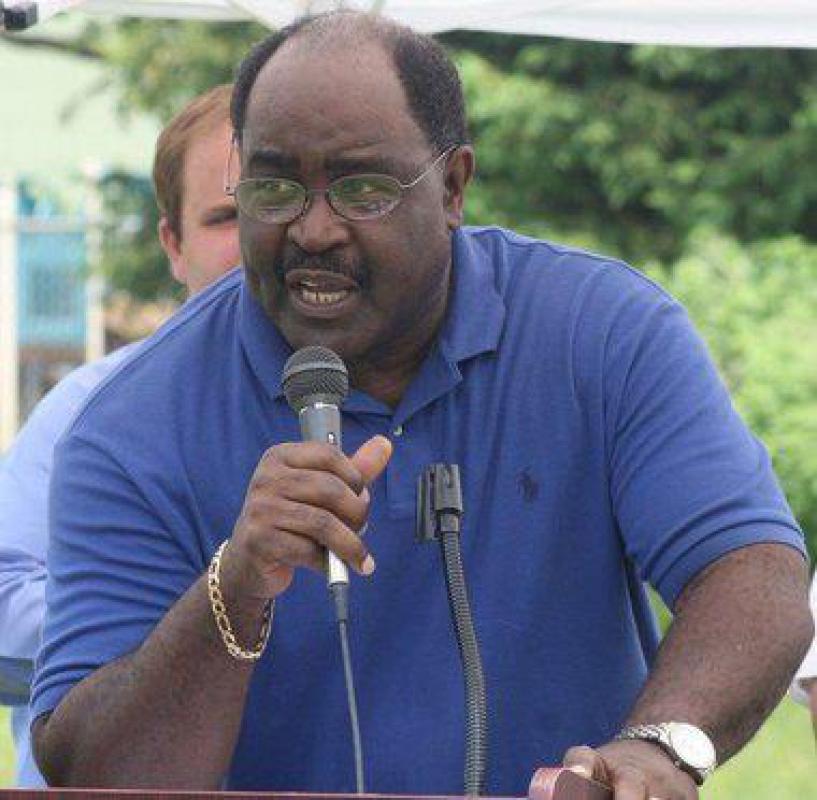

Melvin Edwards, Ward 3 City Councilor in Springfield, says he welcomes the statewide per-person donation increase because campaigns cost money.

“The reality is that all campaigns run on money — no one gives me yard signs for free,” Edwards says.

Setting the right cap

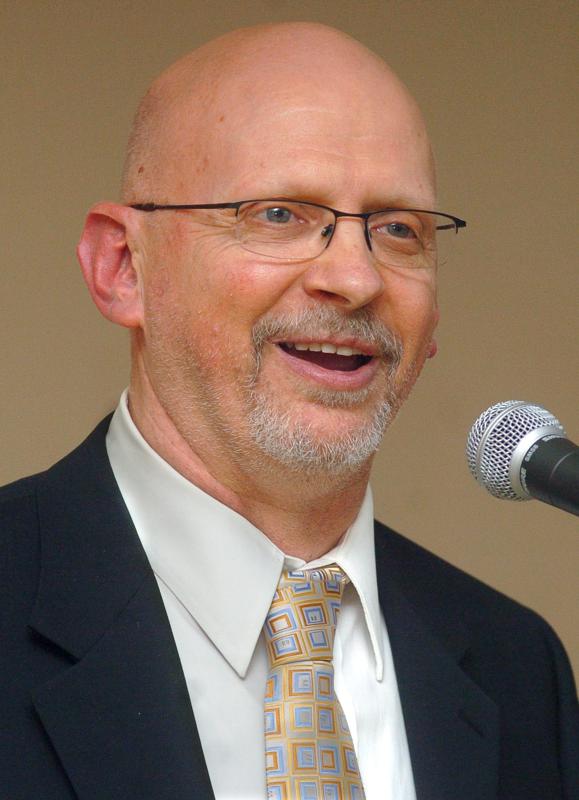

Jay Fleitman, chairman of the Western Massachusetts Republicans, says he believes governments should be involved as little as possible with limiting how individuals spend their dollars.

“How somebody spends their money is every bit as much free speech as free speech is,” says Fleitman. “People should have the right to use their money as they see fit.”

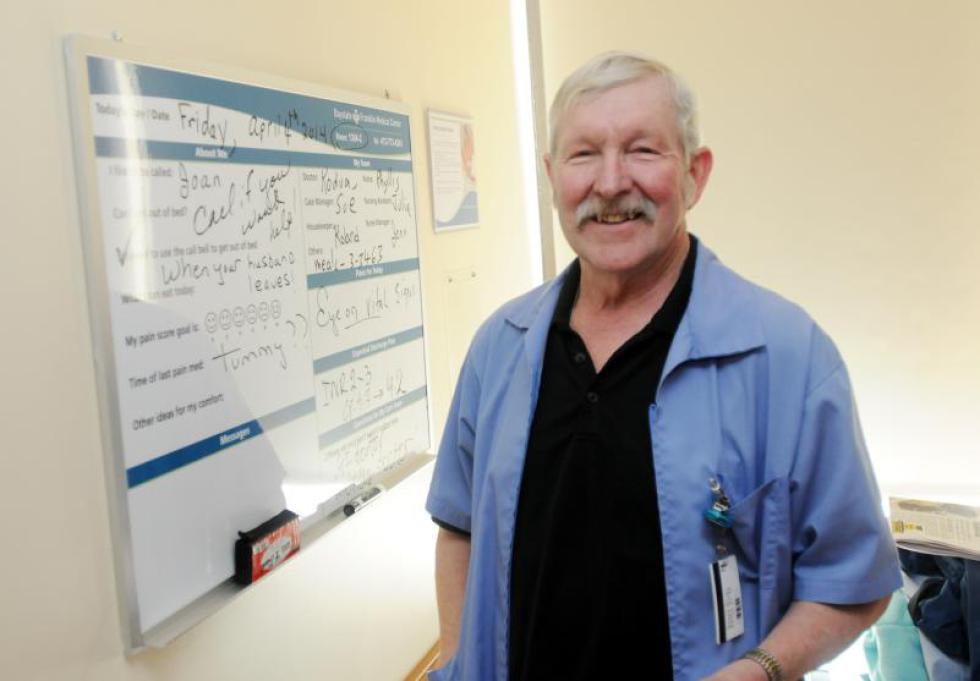

Ray La Raja, political science professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, says an uneven political donations playing field is par for the course.

“Right now we have a situation where outside groups can raise and spend as much as they want, candidates are coordinating to get help from outside groups — it’s a mess right now. It’s basically a lot of rich guys pushing their causes and their candidates,” La Raja says of the state of campaign finance reform.

La Raja says smaller cities like Greenfield and Northampton are somewhat below the radar when it comes to contribution caps, but in bigger and higher-stake cities like Springfield, low limits for campaign contribution can be just as bad as limits that are too high. Low caps, La Raja explains, mean that candidates have to put more effort in to compete with their opponents, which can lead them astray.

“Having low contribution limits with a Supreme Court that says outside groups can spend as much as they want is a recipe for disaster. Campaigns cost money,” La Raja says, adding that less time spent lobbying for money means more time for elected officials to do their joba.

La Raja says a lot of work needs to be done to get things where they should be.

But where does that leave smaller cities like Northampton and Greenfield? Northampton City Councilor Ryan O’Donnell says at the very least, they can be setting an example.

“In general, I think raising campaign limits is the wrong direction to go,” says O’Donnell. It’s up to Northampton to show the state and the nation “how it should be.”•

Amanda Drane can be contacted at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.