Not much is known publicly about Charlie DiRosa. He’s 27 years old. He lives in Chicopee. He has a tattoo of the word TABOO across his throat in thick, rainbow-colored block letters.

And no one but DiRosa knows what he was thinking on Dec. 21 when he posted “Put Wings On Pigs” to his Facebook page.

But that simple act is at the center of a controversy that raises some pressing questions about freedom of speech online, the interpreting of threats, and the evolving presence of police on the web.

On the night of the 21st, detectives from the Chicopee Police Department showed up at DiRosa’s door. Someone had alerted the police that DiRosa had used the phrase on Facebook. Those words, which refer to the act of sending police officers to heaven, are the same ones that Ismaaiyl Brinsley used on social media one day earlier, right before he allegedly shot and killed two NYPD officers in Brooklyn.

After paying DiRosa a visit to look into the possible threat, the detectives decided not to arrest him. The department is, however, seeking a criminal complaint against DiRosa for threatening to commit a crime. On Jan. 12, DiRosa will have a chance to clarify the thinking behind his Facebook post if he appears at a show-cause hearing in district court.

In the meantime, questions about speech rights abound. Officer Michael Wilk, the Chicopee Police Department’s public information officer, said he understands the importance of free speech.

“You do have freedom of speech, but you have to be careful,” Wilk said. “In this case, it was one day after two cops were executed. We looked at it as a possible threat.”

Detective Captain Lonny Bacon runs the station’s detective bureau. It was his call, in conversation with Police Chief William Jebb, to dispatch detectives to visit DiRosa.

“We couldn’t just leave it alone, especially with what’s been going on around the country,” he said, referring to tense relations between citizens and police over the past few months. “People have the right to express themselves, but with a crime like a school shooting, for example, there are sometimes advance signals that might not get followed up on.

“Sometimes when you go further than necessary, people think you’re overreacting and stepping on people’s rights,” he added. “But if this person goes off and does something, people ask us why we didn’t see the signs. We have to think of what the worst-case scenario would be.”

Potential threats of this nature, Bacon said, do come up on Facebook with some regularity.

“Sometimes people act like tough guys behind computer screens. That’s not the same as being a tough guy behind a weapon, but we have to look into the possibility.”

Since the case is still open, the written incident report from the detectives’ visit with DiRosa is not yet public.

DiRosa is nowhere to be found, at least for now. He has pulled down his Facebook page. He hasn’t spoken with the press. Attempts by the Advocate to root out his contact information — through social media, public records searches, and calls to people who share his last name — have been unsuccessful.

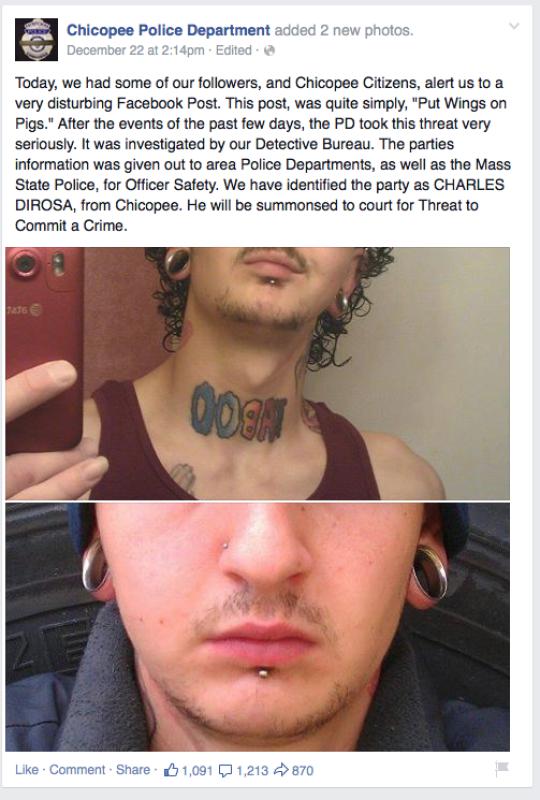

And no wonder. The day after Chicopee Police detectives visited DiRosa, the department posted a public alert on its own Facebook page about him.

“Today,” read the post, “we had some of our followers, and Chicopee Citizens, alert us to a very disturbing Facebook Post. This post, was quite simply, “Put Wings on Pigs.” After the events of the past few days, the PD took this threat very seriously. It was investigated by our Detective Bureau. The parties information was given out to area Police Departments, as well as the Mass State Police, for Officer Safety. We have identified the party as CHARLES DIROSA, from Chicopee. He will be summonsed to court for Threat to Commit a Crime.”

In addition to area departments and the state police, the advisory also went to the Commonwealth Fusion Center, which distributed the information, and a photo of DiRosa pulled from Facebook, to every police department in Massachusetts. In the notice, officers are encouraged to “use extreme caution” in DiRosa’s presence.

The alert hit local TV and print news, which also ran DiRosa’s picture. It is the picture in particular — a bored-looking selfie showing the tattooed DiRosa wearing a Nike knit hat and gauges in his ears — that features prominently in the thousands of responses from online commenters.

“This dude should get locked up just for looking like a clown,” wrote Facebook commenter Jack-Daniels Ceitinn below the Chicopee PD’s DiRosa post. “Looks like an innocent law abiding citizen (insert sarcasm),” wrote Joe Mogo.

Many others expressed their gratitude to the police for publicly spotlighting DiRosa. “Be safe CPD and get this trash off the street,” wrote Phil Tomaszewski.

The internet is not a friendly place, said Officer Wilk.

Wilk grew up in Chicopee, and he has been with the force for 23 years. Last June, the department created this position for him. One of his primary tasks is to run the department’s Facebook page. When he got the tip about DiRosa, he shared it.

“We don’t do it to ridicule people,” he said. “We’re not trying to embarrass anyone. We just want people in the community to know about it. It’s about awareness.”

Things took another turn for the strange when Wilk started getting calls about Doug Humphrey, a retired police officer living in East Windsor, Conn., who shared Wilk’s initial Facebook alert about DiRosa on his own Facebook page, along with a recommendation that any of his “law enforcement friends” who encounter DiRosa should shoot him on sight.

Humphrey, who retired in 2006, never worked in Chicopee. Still, Wilk said, “I was getting all kinds of messages about this guy. I finally went and looked him up. But he has nothing to do with us. He’s East Windsor’s problem.”

“It was dumb on his part to do that,” Wilk added. “Everything right now is too volatile to make comments like that.”

Humphrey was not immediately available for comment.

Times are tense indeed, said Sut Jhally, the executive director of the Media Education Foundation in Northampton. But threats are made online all the time, and they do not each receive equal attention.

“Look at sexual harassment and threats against women,” Jhally said. “Many worse things than ‘Put Wings On Pigs’ get said online, and they don’t draw anyone’s attention. That’s freedom of expression. But as soon as there is even a minor threat against the state, that’s when there is a response. That’s the really worrying part.”

Which raises the question: Was DiRosa actually making a threat?

Many who have been following this story think not. Among the negative comments about DiRosa on social media and news sites, some have expressed their disapproval of the response from Chicopee law enforcement.

“If this charge holds up in court or he is railroaded into pleading guilty to anything, it will set a dire precedent for freedom of speech,” wrote Jim U Lacrum on Chicopee PD’s Facebook. “Regardless of how you may feel about this guy, there is no crime here.” Commenter Chris Savo wrote to the police department: “CPD you are wasting police resources, court resources, and taxpayer money pursuing something that is not prosecutable.”

Bill Newman, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Western Massachusetts office, suspects this may indeed be what the court clerk determines at the hearing. The ACLU does not represent DiRosa, but Newman has been following the story in the news. So far, he hasn’t seen any facts presented that would substantiate a claim that DiRosa was making an actual threat.

“We need to start there,” he said. “In and of themselves, the words are not a crime. They may reflect terrible judgement, gross insensitivity, and be subject to criticism for myriad reasons. But that doesn’t make them a crime.”

Even if DiRosa were advocating illegal action at some indefinite future time, Newman said, his post can’t be criminalized. In his view, four words in quotation marks is more akin to a hashtag or a reference to a trending phrase than it is to a specific call to action.

Eugene Volokh, too, suspects that DiRosa’s comment is likely protected by the First Amendment. Volokh teaches free speech law at the UCLA School of Law, and he wrote about the DiRosa case recently on a Washington Post law blog called The Volokh Conspiracy.

The Chicopee police aren’t wrong to investigate something that they may not end up prosecuting, he pointed out. But as he sees it, DiRosa’s words do not seem to be intended to produce imminent unlawful conduct.

The definition of “imminent” conduct, he explained in a phone interview, is not entirely concrete, but it has to refer to some specified time in the immediate future.

Those details matter, he said. If a bunch of people are standing in a mob outside someone’s house, and someone says, ‘We should burn that guy’s house down,’ that might be an incitement to violence. But if they say the same thing at a bar, or a golf course, or online, it wouldn’t necessarily be incitement.

Volokh also shrugged off the idea that freedom of speech issues are becoming more complicated in the digital age, when statements on the web can float untethered from clear intentions. “Lack of clarity in human motives has existed as long as human speech has existed,” he said. “Context will always change and affect meanings.”

Jhally, the media education director, has seen this story play out before. This past week, he’s been reading news from England detailing the rise in that country of criminal cases against online political speech.

“These aren’t just slaps on the wrist. People are going to jail for that they write,” he explained. “This is supposed to be a society that values freedom of expression. But we’re finding out that the freedom is only sometimes.”

Questions of personal freedoms, he said, often become more pressing during times when the public feels anxious around issues of violence and authority. Following the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of the police — and now Brinsley allegedly killing officers in retaliation for Brown and Garner — this is very much that time in America.

“And it’s now that we see more clearly that the state does not, in fact, have a lot of sympathy and tolerance for freedom of speech, Jhally said.

Equally worrisome, he stressed, is how little most citizens seem to be concerned with issues of individual freedoms. “As if this is a perfectly valid thing for the police to be doing. The idea that posting four words online can lead to this … People should be absolutely outraged.”

Interestingly, one case about online violence actually has been getting quite a bit of attention lately, said Karen List, a professor of journalism and law at UMass Amherst.

In Elonis v. United States, which is currently before the U.S. Supreme Court, a man is appealing a conviction for threatening his wife over the Internet. Elonis posted what were deemed violent threats against his wife, who had recently left him, on his Facebook page.

“The Supreme Court is being asked to decide whose perspective counts here,” List said. “Should the standard be if Elonis intended to threaten his wife, or if a ‘reasonable person’ would feel threatened by the language he used, regardless of his intent?”

But unlike the violent words Elonis wrote, the phrase “put wings on pigs” is hard to read as a direct threat, she said. “Because the words are not specific and not directed at any individual in particular, they most likely would be considered protected speech.”

Some think of DiRosa’s story as one about threats to police, but others will see it as a story of threats by the police. But in what List calls the “vibrant marketplace of ideas,” only true threats can be criminalized.

DiRosa isn’t the only person whose online words have riled cops. In May 2013, a high school student in Methuen named Cameron D’ Ambrosio was accused by local police of making “terroristic threats” online. Those incendiary words, post by D’Ambrosio on his Facebook wall, read: “fuck a boston bombinb [sic] wait til u see the shit I do, I’ma be famous for rapping, and beat every murder charge that comes across me.” D’Ambrosio, it turns out, is an aspiring rapper, and he wrote this as a verse for one of his songs. The indictment was rejected by a grand jury, and D’Ambrosio returned home in June, after being held in jail for a month without bail.

Evan Greer remembers that case well — as the campaign manager for the Boston-based Center for Rights, she advocated for all charges to be dropped. An online petition for D’Ambrosio’s release, which she created in “about an hour,” was viewed by more than 1 million people in its first 24 hours, and generated over 90,000 signatures.

“When you’re working to defend freedom of speech, you always have to defend it at its edges,” she said.

As a musician herself, Greer took the D’Ambrosio case personally. “ I post inflammatory political lyrics of my own online, and no one’s arrested me for it.”

Greer sees strong parallels with the DiRosa case, calling it “chilling.”

“If people are pausing before they share something because they think they might get a knock on the door, that has a severe effect on how free we feel in expressing ourselves.”

Updating and maintaining the Chicopee Police Department’s Facebook page has brought him up close to a lot of angry, dissenting voices in the wake of the DiRosa story.

“Our Facebook blew up,” he said. “I have no problem with lively debate, but I have to delete comments on our page sometimes, and I had to do that a lot over Christmas and New Years. People were posting links to pictures of flying pigs and dead cops. I delete those.”

Wilk can do this because the Facebook page isn’t a government page — it’s protected by Facebook’s terms of service, which allows Wilk full reign to moderate and delete offensive posts.

“We have kids that come to the site,” he said. “People come to the site in support of police. They don’t need to see pictures of dead cops.”

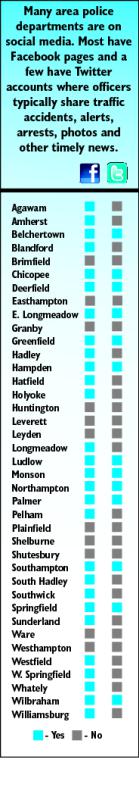

When it comes to best practices for engaging with the public, social media is still fairly untested water for many police departments, said Wayne Sampson, executive director of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police.

The association, which is based in Grafton, does not provide a formal written policy on social media guidelines for police departments, Sampson said. “But we do recommend that any department who starts it up has a written policy.”

Sampson has been following Elonis v. United States with some interest. He said he is eager to see whether the ways that the police define online threats will change as a result.

“It’s very timely. The nation is so concerned right now with freedom of speech relative to police officer safety. It’s a very difficult line to walk.”

Sampson is quick to add that reacting to each case requires context. When someone like DiRosa makes a comment, he said, the police have to look for the potential for reality in that threat. Is the threat made on a particular police department? If so, does the person have access to the officers there? Does the person have direct access to weapons? What is his history? Have there been violent incidents in the past? Is the new threat immediate? Such questions, he said, must be answered as quickly as possible.

The rationale behind DiRosa’s behavior is his to explain. At the hearing later this month, he may make his motives more clear. Until then, the person whose words stirred up a frenzy of speculation seems to be the only one who isn’t talking about it.•

Hunter Styles can be reached at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com