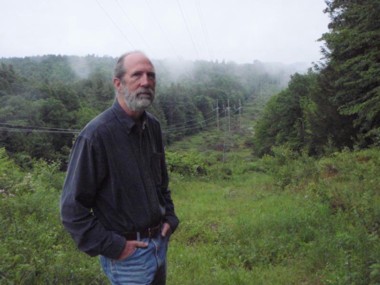

Jim Cutler lives in the hilltown of Ashfield, known as the “Little Switzerland” of New England for its mountain views, and runs a small solar-thermal heating company. To Cutler, the 36 acres on which he settled three years ago are the pot of gold: just the home he wanted.

“I wanted arable land and water,” he says. “I didn’t want to be in a flood zone or on land with a potential for flooding. I don’t farm. I garden and I have a small orchard with Asian pears, peaches and apples. I’ve converted the inground pool to a planting bed for a vegetable garden and around the edge I planted perennials. It’s just ornamental.

“The property on the north side abuts the Bear River. That’s a protected habitat [designated as Priority Habitat of Rare Species under the state’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program].” On his land, Cutler says, he sees deer, bear, wild turkey, pheasant, grouse, eagle and redtailed hawks.

Little did Cutler know when he settled on his thickly forested acreage that this year a call for more energy infrastructure in the region from the governors of the six New England states would bring Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. to northern Massachusetts. Now Cutler, like other landowners in Berkshire and Franklin counties, has found himself in the sights of one of the nation’s largest energy transmission companies as it proposes to build a pipeline from western New York to Dracut, Mass., near Lowell.

Representatives of Tennessee Gas did not notify Cutler before trying to make contact with him, he says. Instead, “They did come to the house physically, at a time when I was not here. I did not solicit them. They came to the house to get my permission to survey the land, but I have not granted it. They want to do normal line-of-sight surveying. They want to take soil samples and they want to drill into the soil. They’re doing an archaeological survey and they’re determining if it’s a wetland and they want to know what’s the chemical content of the soil—those kinds of things.”

Eventually, Tennessee Gas wrote Cutler several letters to ask permission to do the surveying. “Each letter is a reiteration of the original,” Cutler says. In the final letter, the company warned him that if it did not receive permission, it would petition the state Department of Public Utilities.

Cutler was not offended because the company stated its intention to petition the DPU. “I tend to not let those kinds of statements rile me,” he says. “I can keep them in perspective. I know that they have to go through a process. That just tells me they’re willing to go through that process. I’m willing to go with them head to head through that process. I know what I would have to do legally, and I know there’s a tremendous amount of support behind me from other landowners and that I’m not alone.”

Cutler is indeed not alone. Landowners all along the pipeline’s proposed route have taken the same stand he has. Fifteen towns and more than a dozen organizations, from the Conservation Law Foundation to the Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions and the Mount Grace Land Trust, have gone on the record supporting the concerns of area residents who say the pipeline is destructive to the environment and dangerous to life and property. A region with numerous wetlands and areas rich in wildlife, they say, is not the place to build a gas pipeline. The Audubon Society has refused to allow Tennessee Gas access to its 1,600-acre sanctuary in nearby Plainfield (“An Ironic Proposal,” May 21, 2014).

“Twenty-one acres of my property are under a conservation restriction through Franklin Land Trust,” says Cutler. “It’s mostly forest. The pipeline would be going through that area. There are wetlands; however, the wetlands aren’t really in the area where they want to put the pipe. But the wetlands are not far—I would say a couple of hundred feet.

“My property comes up against the Bear River. The WMECO [Western Mass. Electric Company] power line comes above the upper level of the land before it begins to slope down to the river. At the edge of the woods there will be a 100-foot cleared path for the pipeline construction. In the beginning, they need that 100 feet to get the cranes in to lift the pipe and drop it into the trench. Then they only have to maintain a 50-foot section, 25 feet on each side of the pipeline.”

Worse than seeing his property, with its rich ecology, scarred with a 50-foot-wide pipeline is the danger the pipeline might pose, and the disturbance caused by the company’s patrolling of it, Cutler insists. “These pipelines have a capacity to leak and ignite and explode, so there’s a large incentive on the parts of the company to do flyovers to inspect,” he says. “They’re looking for things like dead patches of grass, and there are instruments to pick up the methane that may come from the leak. They do that three or four times a year. So the disturbing of tranquility is a huge factor. And there’s the heat signature from a pipeline explosion. It explodes and there’s a huge flame that goes for a while until they shut the gas off. The proximity to that point is very important. My neighbors—the pipeline is going to go within 100 feet of their house. They probably wouldn’t survive an explosion.”

Cutler’s concern for his neighbors and others along the route mapped for the pipeline led him to study the project and ensure that no one would be caught unaware when Kinder Morgan, Tennessee Gas’s parent company, began serious negotiations with state and federal agencies that might lead to property takings by eminent domain.

“When I first heard about them coming here, when they started contacting my neighbors, that’s when I started getting information,” he says. “But what I wanted to do was to put together the information in a way that was factual and non-emotional, non-political. I went to the assessor’s and I got a list of all the other people that were abutting the pipeline. My desire was to educate the landowners here in Ashfield and let them decide what to do. That propelled me into a process of giving presentations to selectboards and larger and larger groups.

“We’re part of MassPLAN, the Massachusetts pipeline awareness network. We’ve now put together a legal team. We have about eight lawyers who have agreed to be the team for this fight. We have momentum on our side. We’re way out ahead of this. Kinder Morgan hasn’t even filed anything yet.”

Fueling resistance to the pipeline yet more is the recent announcement that ratepayers may be assessed to pay the estimated $2.7 billion it will cost—and for a pipeline they don’t need, given the state’s plans for the expansion of alternative energy here, opponents say (“After Coal: The Frackiing Paradox,” June 12, 2014).

“The industry says that we need it. The industry is compromised because it has something to gain,” says Cutler. “Then to have a tariff and make everybody pay for something that people out here don’t even use—this problem can be easily solved by expanding the view of what other possibilities exist.”•