Though we are emotionally close, my brother and I are very different in several regards.

No more so, perhaps, than in his decision to eat vegetarian. Both of us were raised feasting on the works of the greatest chef of all time (our mother), but in his teen years, my sibling turned his back on staples like leg of lamb and spaghetti carbonara.

We might both have settled on Northampton as our new hometown of choice, but when I go out to eat, I’m hungry for the hash of the day at Jake’s or a steak at Caminito. These are not joys I’ve ever shared with my brother.

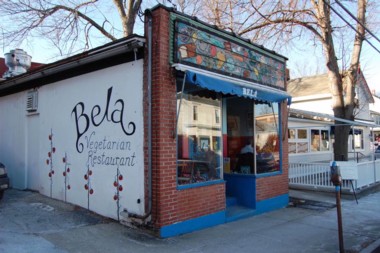

Conversely, I know little about the longstanding culinary relationship my brother and his family have with Bela Restaurant at 68 Masonic Street.

In restaurant years, Bela has been around forever. It opened in 1991.

You might know of some other institution that has been around longer, but how many have had the same person working the 10-burner stove the whole time? Lily Olpindo was even cooking there when it was known as The Fez, an early macrobiotic restaurant.

The long, narrow brick box of a building with its huge plate glass windows and striped awning up front looks as if it could once have been a small grocery market, selling mountains of fresh, raw produce from across the Valley. That’s not far from the truth. The produce is locally sourced (Paddy Flat farm in Ashfield and Red Fire Farm in Granby are among the many local farms Olpindo works with). The whole place is permeated by the smells bubbling up from her stove. This odor is Olpindo’s medium.

“I don’t taste the food as I cook,” she said, explaining that when she samples the food, she’s prone to over-tweak it, striving for some ideal taste. “I smell it, I see it and I can tell if it’s good. I don’t keep recipes. Every time I make a dish, it’s a little bit different.”

When the opportunity to buy the business arose, she jumped at it, renaming the place Bela, a loose acronym for her name and the names of her mother and her sisters—the people she first learned to cook with and who remain in Manila, Philippines, where Olpindo was born and raised.

My brother has been eating at Bela for over a decade, but when I asked him about the menu, he laughed.

“I’m not sure I’ve ever seen it,” he said. “I probably have, but I don’t remember it.”

A hallmark of Olpindo’s restaurant is its ever-changing specials board. Every day there’s something new, and my brother and his wife have never been disappointed (though occasionally they’ve been envious of what the other has ordered). My brother appreciates that in their preparation and presentation, Olpindo’s meals gain complexity and interest from the careful pairing of a few well-chosen and sometimes unlikely ingredients.

This sense of delicate innovation also influences her wide variety of salad dressings, which seem to be consistently unusual yet perfectly suited to whatever combination of greens is being served.

The one dietary trait we share, my brother and I, is a love for healthy-sized portions. And by that I mean big. I was assured that in this department, Bela doesn’t skimp. Further, he assured me that Bela can handle any dietary restriction he’s come across, with scrumptious results.

I’d been to Bela a few times myself and enjoyed it, but when I went to meet with Lily Olpindo to learn more about her background and her restaurant, I was mostly driven by the enthusiasm of others. I wondered about what we’d talk about. Like a Catholic visiting a Muslim, I hoped I could avoid processing everything she said through the prism of my own (flesh-eating) faith.

As we sat down at a table just outside her kitchen and I got ready to discuss the merits of kale and tofu, Olpindo smiled and surprised me.

“I’m not a vegetarian,” she said before I’d fired off a single question. I blinked and asked her to repeat herself. She did, adding that while her restaurant was completely vegetarian, she often found inspiration for new flavors from what’s served to meat eaters.

“Vegetarian cookbooks bore me,” she said, enjoying my shock. She prefers looking at recipes for omnivore dishes to get new ideas, figuring out how she might translate the meat flavors to her palette of ingredients. A vegetarian variation on teriyaki is a recent favorite.

When asked if she’d had any recent inspirations from the other side of the culinary divide, she pointed to one printed in a magazine from Max Burger in Longmeadow.

“My partner and I went down to try the candied bacon recipe,” she said. “It was amazing.”

To help support her family, Olpindo left home at 19 to work as a nanny. She lived first in London for a couple of years, then in Florida. She cooked meals for the children and also for their parents, sometimes for formal occasions. In 1987, she moved north to New England.

“At the time,” she confessed, “I had no idea where I was going.” She’d seen an ad for a cooking job in a newspaper and thought, because the area codes were similar, that Massachusetts was somewhere near San Francisco.

Her menu doesn’t necessarily reflect her Philippine background or any specific ethnicity. It’s more tailored to foods she likes cooking and her patrons enjoy eating. There is an Asian flair to some staple offerings—miso soups and many noodle-based dishes—but the source of her never-ending parade of satisfying specials is maybe less exotic.

“Really, it’s whatever is in my walk-in that day,” she says with a laugh.

She’s developed several long-standing relationships working with local farmers to source the freshest seasonal ingredients. But many times inspiration is born just as much of economy and efficiency. She hates throwing food away and enjoys finding alternative, unexpected combinations of what’s on hand.

Commanding her own small kitchen, each day she assembles a menu intended to offer patrons a breadth of possibilities while keeping the plates moving. Unless there are health concerns, she requests there be no substitutions. If a diner wants something slightly different, she charges a $5 substitution fee that is donated to a different charity each month. The restaurant operates on a cash-only basis.

Because smell is such an important part of her cooking, she asks patrons not to wear fragrances. They are welcome, though, to bring their own beer and wine.

For Olpindo, after reigning over her kitchen for more than two decades, success is clearly more than luck. Like my brother and me, growing up and dining at the table of the world’s greatest chef, those dining at Bela are best served if they follow the rules and let the kitchen take care of them. The lady with the ladle knows what she’s doing; she’ll treat you right.•