It sometimes seems there is no mystery left in our lives these days. In our oversaturated information age, just about anything you can think up has a tutorial video up on YouTube, be it changing a faucet or crocheting a fake beard (4,830 results, by the way). We know the instant our friends get engaged or go into labor, and just how proud they are of that elaborate lunch they prepared.

Art, though, resists our mania for immediacy. Stoic, holding in its secrets, it forces us to decelerate, to pocket our phones and stare, or listen, until what we are taking in becomes something else inside of us. What’s so remarkable about the whole process is that the art itself is so often humble in its composition: even the greatest paintings are still made up of canvas, oil, and ground, colored earth. And yet in an artist’s hands they are made into mystical mirrors, reflecting back pieces of us we didn’t know were there.

To be sure, you can find plenty of oil painting lessons on YouTube too, but none of them is going to make you a master—art just doesn’t work that way. Or does it? This is one of the central questions of Tim’s Vermeer, a documentary from well-known magician Teller (he’s the quiet half of Penn & Teller) screening at Amherst Cinema. The film follows Texas-based inventor Tim Jenison on a quixotic mission to “solve” the mystery of how the 17th-century Dutch master Johannes Vermeer (“Girl with a Pearl Earring”) was able to create his startlingly realistic canvases—with their inconceivably fine gradations of light—over a century before the invention of photography.

Jenison, who made his fortune during the early days of the desktop video boom, has spent years in his pursuit of answers, and what he has deduced could quite possibly change the history of art forever. Others before him have speculated that Vermeer used a camera obscura—sort of an early projector system that would have allowed him to duplicate an image on his canvas before he even began painting—but Jenison goes farther, creating a device that combines the camera obscura with a pair of finely ground mirrors which allows him, despite never having painted before, to create paintings remarkably similar in style to Vermeer’s.

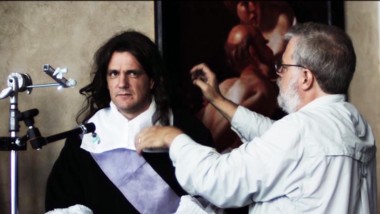

That, though, is just the start. To give his hypothesis the ultimate test, Jenison decides to recreate a Vermeer canvas (“The Music Lesson,” which he travels to Buckingham Palace to see) from scratch, going so far as to build replicas of all of the furniture and objects from the painting, and house the scene in a Texas warehouse. It’s a massive, year-long undertaking, and along the way Teller’s film visits with a variety of artists and art historians, including British artist and author David Hockney, who explains that art and science were much more intertwined in Vermeer’s day than in ours, and that the artist’s neighbor was a master lens maker.

Of course, the results are fairly incredible—if they hadn’t been, it’s not likely we’d be watching—but whether they provide any real insight into Vermeer’s art is another question. The true question that the film poses—but that only a viewer can answer—is about just how strongly technique and vision are intertwined. Does being able to paint like Vermeer make you an artist? Does the notion that Vermeer may have used the technological aids of his day make him less one? And what of that sense of mystery—can we still have meaningful art without it? For his part, Jenison seems interested in the project mostly as an avid geek looking to solve a knotty technical issue. Whatever the answers—and it’s unlikely everyone will agree on what they are—Tim’s Vermeer is a fascinating look at the questions, and the reasons why we ask them.•

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.