Even when electronics weighed as much as boulders and glowed with vacuum tubes, concocting strange instruments capable of new sounds was the province of Frankensteinian basement tinkerers. Though it seems unlikely, electronic sound experimentation arose far earlier than the arrival of synthesizers in pop music 40-odd years ago. It was in the late 1920s that Russian Leon Theremin patented his elegant instrument (also called theremin) that produced electronic sounds via the proximity of the player to an antenna. And Theremin had invented it well before receiving his patent.

Even earlier than that, a peculiar line of inquiry became the obsession of Mary Hallock-Greenewalt, a talented pianist from an unusual background. Her New Englander father was a U.S. consul in the Middle East, where he married a Syrian woman from an aristocratic family. Hallock-Greenewalt spent her first decade in well-to-do circumstances in Beirut, then in 1883 came to the United States. The unpleasant reason for her move was the death of her young mother, who’d been sent to Northampton for mental health treatment. After that death, the young Mary Hallock was sent to her father’s relatives in the U.S., where she completed her education.

Soon she proved adept at piano, and after studying the instrument in Vienna, performed and gave lectures in the United States. She mingled fascinations with music, color, and spirits, as evidenced in a manuscript from a radio lecture, held in the Hallock-Greenewalt collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: “Are you there? Fellow Spirits across space. Are you there Mary and Lucie and Nancy and Susie and David and John? Even though I can’t see you, I know every one of you is ‘all there.’ True Blue.”

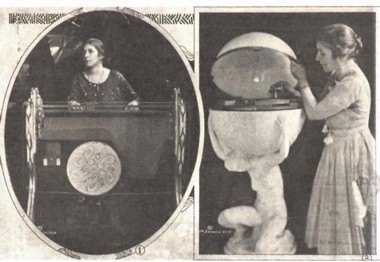

Those fascinations led Hallock-Greenewalt to explore the combining of music and color. She moved from early experiments with tinting film to a phonograph that played sound and emitted colored light in tandem. Finally, her efforts led to a color organ called the Sarabet (after her mother, Sara Tabet), and a color/music artform she called Nourathar. Her prodigious inventive skill led not only to publications, but also to a slew of patents for the technology she created in pursuit of her instrument. That in turn led to patent infringement by major corporations, whom Hallock-Greenewalt sued.

Tangling with them fueled Hallock-Greenewalt’s political involvement. As a member of the National Women’s Party, she spoke out against the corporations who’d appropriated her work. Because she pursued her work outside of institutions, she had an unusually uncompromised view of the corruption that stood in her way. She wrote, “It will be hard for future ages to realize how completely at this time the electric aggregations held control over practically every door of opportunity. My patent attorneys held a retainer fee from the General Electric.”

In an age when something like her color organ is available for download (one such contender is called Coagula Light), and when her idea of musical visualizations is a common part of computer music players, her groundbreaking views seem at once anachronistic and modern: “The eye then as the gauge; the spectral is the nearest in fineness to the spiritual essence man seeks to express through the arts. It is the most perfect. Its apportionment unto color stupendous in its portent.”

This unusual, brilliant and outspoken woman is the subject of a Women’s History Month talk this week at Historic Northampton led by UMass-Amherst communications professor Anne Ciecko.•

“The Light of the Senses”: March 9, 3 p.m., Historic Northampton, 46 Bridge St., Northampton, historic-northampton.org.