A meteor estimated by NASA to weigh 10 tons exploded the morning of Feb. 15 over Russia’s Ural region, and its shock wave caused injuries to more than 1,000 people. It took out windows and walls in the city of Chelyabinsk. And it temporarily shifted the conversation here on earth to talks of the heavens.

“We can find these objects, we can track their motions, and we can predict their orbits many years into the future,” noted Sky and Telescope’s Robert Naeye in an essay called “Lessons from the Russian Meteor Blast.” “And in the unlikely event that we actually find a dangerous object on a collision course with Earth, we might actually be able to deflect it if given sufficient warning time. Now, every government in the world is keenly aware of the possibility of meteor explosions over its territory.”

The Russian parliament is also keen on the idea of a warning system. “Instead of fighting on Earth, people should be creating a joint system of asteroid defense,” wrote affairs committee chief Alexei Pushkov on his Twitter account on the Friday after the blast. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin echoed the sentiment and proposed a global defense system to counter space threats.

And on CNN, Lawrence Krauss, professor of physics and director of the Origin Project, talked about how human technology has advanced to the point of predicting and, more interesting, deflecting oncoming meteorites that could cause the earth “significant damage.” “We have to think about it seriously,” he said. “It’s not science fiction. We can send a rocket out and land on [a meteor] or impact with it.” If the meteor is far enough away, “A small rocket running for a while [can cause] a small angular change… enough to have it miss the earth.” Meanwhile, according to The Guardian, “The University of Hawaii has proposed a cheaper, simpler system known as ATLAS—Advanced Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System—to be constructed with the help of a $5 million grant from NASA.” Its aim is to create a warning system for oncoming asteroids and find ways to save earth from the impact.

So welcome to the age of empyrealization—an age of man’s increasing awareness and interactions with the heavens. We grow cognizant that we exist on intimate levels with the rest of the universe, that we are interacting with it, and, increasingly, having an effect upon it, as it does upon us. The word doesn’t exist yet in the dictionary, but, for that matter, neither did globalization three decades ago.

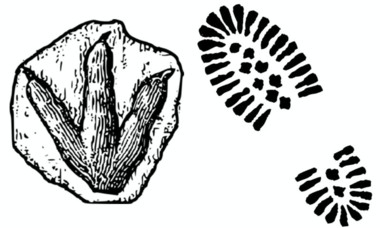

Unlike the dinosaurs, we have, in effect, become active agents in changing our destiny. A giant meteor wiped out 90 percent of life on earth 65 million years ago because the dinosaurs didn’t collectively create a missile shield to deflect the meteor. Humans, on the other hand, with our orbiting telescopes and space probes and our growing awareness of the threat from space, can track large foreign objects coming from millions of miles away, and are talking about collectively deflecting those that could do us harm.

That man has changed his home planet is now well accepted. Long before the industrial revolution and the age of climate change, humans have significantly impacted earth, at least according to climate scientist William Ruddiman. In his 2005 book Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate, he claimed that there is significant evidence that levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have been rising since the earliest beginnings of agriculture. There is strong evidence, too, that a mini-ice age was averted some 5,000 years ago due to the rise in methane caused by the proliferation of rice paddy agriculture in Asia.

Unlike our ancestors, however, we are increasingly aware that human actions have an impact on the entire planet and beyond.

That knowledge informed NASA’s decision in September, 2003 to crash the spacecraft Galileo on Jupiter rather on Europa, one of Jupiter’s 39 satellites. Europa has an ocean under its ice, and active volcanoes to boot. It just might be supporting alien life. Jupiter, on the other hand, is very hot and gaseous and deemed incapable of life. Crashing Galileo on Europa would have risked contaminating it with microbes from earth.

In fact, we have been interacting with the heavens longer than most have thought. Think of it in terms of radio waves. According to Adam Grossman, “Mankind has been broadcasting radio waves into deep space for about a hundred years now. That, of course, means there is an ever-expanding bubble announcing Humanity’s presence to anyone listening in the Milky Way. This bubble is astronomically large (literally), and currently spans approximately 200 light years across.”

Or think of it in term of our orbiting trash. According to NASA, “More than 500,000 pieces of debris, or ‘space junk,’ are tracked as they orbit the Earth. They all travel at speeds up to 17,500 m.p.h., fast enough for a relatively small piece of orbital debris to damage a satellite or a spacecraft.” While some fall to earth, others exit into outer space. In other words, the cosmos might rain meteors on earth, but humans, too, have already interacted with the universe by sending manmade debris into space.

More significantly, our rovers have been on Mars, roaming and digging and studying the soil. And we have plenty of space probes that travel about in our solar system. Voyager 1, the first space probe sent up to the cosmos, has gone outside the solar system and into deep space. China, meanwhile, is contemplating a permanent colony on the moon.

And all the while we map the universe, searching for planets that may be hospitable to life. Astronomers, in fact, have discovered hundreds of other solar systems, and 864 exoplanets so far—planets that are outside our solar systems. One planet in particular, 150 million light years away, is believed to have an atmosphere.

Clearly our destiny lies in outer space. In a sense, globalization is child’s play compared to empyrealization, where man now recognizes Earth as existing in an open system with the rest of the cosmos he is interacting with and, increasingly, affecting.

Alas, back home, there’s the issue of falling meteorites. The dinosaurs didn’t fare well. Man, on the other hand, has a better chance. Whether or not we can deflect a large meteor, as in the Hollywood movie Armageddon, remains to be seen. But brilliant minds are at work. And there’s nothing like an external threat to galvanize humanity.•