If you’ve spent any time in downtown Northampton, you’ve no doubt passed the impressive facade of R. Michelson Galleries. That imposing structure houses, at present, a remarkable collection of work by children’s book illustrators (on view into January). Wrapping up this week, however, is a concurrent exhibition by illustrator Barry Moser marking the 30th anniversary of his luminous version of Alice in Wonderland.

Moser was the first artist Richard Michelson represented, and it’s easy to see why Michelson wanted to. Moser’s engravings are masterful: the linework creates mesmerizing textures, and there’s a combination of realism and just-off-kilter composition that imbues his fantasy worlds with a weird sense of reality, as if the improbable denizens of this literary realm really exist somewhere. It could not be clearer that these are works by an artist and craftsman of the highest order.

The 1982 Pennyroyal deluxe edition of Alice is hardly an easy thing to come by—it’s currently found for several thousand dollars—though far less expensive printings do, thankfully, exist. You can see the book at R. Michelson, surrounded by original drawings and engravings. The works on the walls quickly reveal some of the complicated process of getting from imagined image to printed page.

Michelson says that the impressive textures and renderings are, for Moser, relatively quick to execute. He goes on to explain that Moser’s process involves extensive planning, posing of models, and particularly careful choosing of models—it’s become a Moser trademark to use those choices in a sometimes subversive way. In his Alice, Humpty Dumpty’s face bears the doughy nose of one Richard Nixon. In a 2012 re-do, Moser offers the snarling visage of a more recent “Tricky Dick,” Dick Cheney.

Other faces might well be familiar—the models include Moser’s daughter Madeline as Alice, children’s author Jane Yolen as the White Queen, and Winston Churchill as the Rabbit.

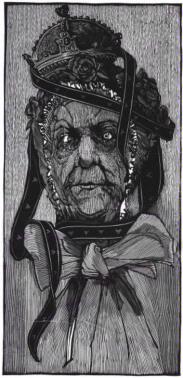

A few of the images seem to bear extra marks, as if Moser got weary of the exactitude and threw in a few postmodern scratches to remind viewers that this is artwork, the product of a fallible process. Which would indeed be an interesting choice (these marks are visible in the Queen of Hearts, pictured). But it isn’t quite so. Michelson Galleries’ Paul Gulla offers the bigger story, one which, he says, Moser himself commented on in the Pennyroyal book.

Gulla explains that engraving used to be done on boxwood, a commodity that’s now too expensive to be a feasible choice. Gulla says boxwood, in addition to its current scarcity, has to be treated properly in order to withstand the three tons of pressure applied in the printing process. Moser got his boxwood from a supplier in London, England, and complications led to his batch of boxwood blocks falling shy of the ideal drying time. What at first appear to be stray marks are in fact cracks, cracks which appeared after Moser had completed the 70-something prints for the book. He turned down the supplier’s offer to replace the blocks, opting instead to embrace the look.

And, though it may be the product of an accident, in certain works in particular, the cracking seems to enhance the final product, offering just enough of a reminder of the nature of the medium. The cracks sometimes break up the march of tiny lines in such a way that it’s easy, at close range, to dispel the illusion of the finished image and envision the artist laying out those tiny grooves to make a mere block of wood yield stunning detail.

The exhibition ends soon, but dropping by to check out Moser’s work firsthand is well worth the time.•

Barry Moser: Alice: through Dec. 15, R. Michelson Galleries, 132 Main St., Northampton, Northampton, (413) 586-3964, RMichelson.com.