For years, countless live sound engineers struggled to keep up with not only the growing sizes of audiences and performance venues, but also the broad range of acoustic and sonic challenges that such performances present. The Beatles famously opened their 1965 tour of the United States with a performance for a crowd of over 55,000 at New York’s Shea Stadium, using a sound system roughly the size of something you might find in a local club today. The cacophony of screaming teenage girls who had packed the stadium made it nearly impossible for anyone to hear the band play, including the band members themselves, and many have postulated that the experience fed directly into the Fab Four’s decision to end live performances a year later. Subsequently, sound engineers scrambled to design and engineer sound systems capable of producing a decent-sounding show in such huge arenas as would become the norm for the epic-scaled rock bands of the 1970s.

At some point, of course, this was achieved. The Grateful Dead may have perfected the equation with the 1974 debut of their infamous “Wall of Sound,” which not only brought clear, sharp audio to every corner of even the largest stadia, but also was equipped with an equally robust monitor side to ensure that the band could hear everything just as well as the audience. Of course, such grandeur had its practical downside; at approximately 75 tons, the components of the Wall required four semi-trailers and 20-plus crew members to haul it around, and setup/breakdown time was considerable. Eventually, even the reality-bucking Dead were forced to pare down the monstrosity and tacitly admit that perhaps the notion had been overkill.

These days, the holy grail of perfect sound seems almost to have been reversed. The popularity of “unplugged” performances and the advent of widespread home recording setups has seen a spike in demand for things that—perhaps in a blasphemous denial of all things rock ‘n’ roll—offer a musician or sound engineer a maximum level of control over every shape and tonal contour of sound, but also—perhaps most importantly—over volume and recording level. To that end, the musical equipment market of the last decade has seen an explosion of things like digital “cabinet simulators,” which can reproduce the sound of a cranked stack of Marshall amplifiers or a tube-packed Mesa Boogie turned up to 11—but at a very low volume.

Almost a personification of this new aesthetic, longtime Valley fixture and Louisiana transplant Chris Ryan has always been a subtle but powerful musical force in the Valley, from drumming for bands and artists like Mary’s First, Tom Ingram and Frank Manzi to being involved in operations like Big Bang with Tommy Pluta, which duplicated and mastered many demo tapes and CDs for Valley bands in the 1990s. Ryan is also something of a technical wizard and design innovator, having worked for decades on digital drums as a sound designer for Ddrum and Kat, companies that helped pioneer digital drum technology. Now, in something like a return to his more acoustic percussive roots, Ryan’s hit on something, well, quieter.

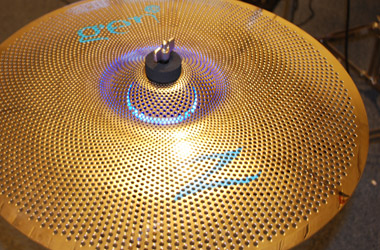

The Zildjan A-E (Acoustic-Electric) cymbal system combines the best of both technologies, beginning with cymbals that are fabricated from a custom alloy and perforated with thousands of tiny holes that radiate outward in what Ryan describes as “something like a Fibonacci pattern.” That is to say, the holes get progressively larger toward the cymbal’s edges, assuring smooth tonal characteristics throughout its surface, adding more sustain and increasing overall durability. The practical effect of this is to make the sonic output of the instruments 70 percent quieter than traditional cymbals while still preserving the feel a drummer has when playing them.

“That way you don’t bug your neighbors so much,” Ryan says with the smile of someone who’s likely fielded a few noise complaints.

The second part of the AE system is comprised of a specially designed microphone (complete with cool glowing blue light) and software package that allows the cymbal’s organic sound to be electronically processed according to a vast set of customizable parameters that are controlled by a simple interface unit. This unit allows musicians, producers, engineers and live sound technicians to shape the ultimate sound into any number of final outputs, effectively turning a single cymbal into several. The interface unit also connects to any computer via USB cable and accesses new sounds and software updates as needed.

“It’s a similar process as [is employed by] an electric guitar,” Ryan explains. “An electric guitar has a low-volume string—you put a pickup under it and you amplify it. Then, you use your amp settings or foot pedals to shape its tone.”

While many electronic drum kits offer a similarly vast range of sound options, the AE system differs in its creation of them in two notable ways: number one, all other electronic drum systems use only digital samples of live drums and cymbals from the get-go. While sampling technology has become extremely good over the years, it’s still not a sound that’s created organically or “live.” Secondly, even the best-sampled cymbal sounds, up to this point, have had to be triggered by hitting some sort of wired rubber pad, which most drummers will tell you does not feel like hitting a cymbal.

“Being at low volume, you have the real metal, so it feels good,” Ryan explains. “It’s much more comfortable to play, and you get the same rebound that you do with a traditional cymbal.”

He goes on to note that for live applications, the drastically reduced overall volume of the perforated cymbals also allows you to forego traditional, but not ideal, methods of volume reduction:

“If you’ve ever been in a band and been playing in a small room, sometimes the cymbals are just the loudest things. We’ve all done those gigs, and so then you would have to use Blasticks or brushes to lower the volume. Now that you have a cymbal that lowers the volume, you can still play with regular sticks, you can play with same intensity, and still drive the band.”

Zildjan is the oldest musical instrument manufacturer in America (based in Norwell, Mass.). Ryan, along with a team of other designers, put together the AE system for the company only a couple of years ago, and it’s been on the market for about half that long, sold under the Gen-16 product line (www.gen-16.com). It’s already garnered awards, including a “Best in Show” award from the annual National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) at its annual conference in Anaheim, Calif. and a MIPA (Musikmesse International Press Award). It was called “the most innovative drum product in 400 years” by Electronic Musician magazine.

Several touring European bands are using the AE system, as are Devo and backing drummers on American Idol. The percussionist for Enrique Iglesias is onboard as well, and Russ Miller, a session musician who plays with Italian opera tenor and classical crossover artist Andrea Bocelli, apparently values the product for yet another reason: its ability to project subtleties.

“Because of the application of the microphone, he’s able to play really subtle things with brushes on the cymbal and hear it in a massive arena,” says Ryan.

Ryan continues to gig up to four nights a week in addition to his often demanding schedule of traveling to trade shows, giving product demonstrations and helping new customers set up their new toys, but he’s up for it.

“I’m playing all the time, man,” he says with the smile of someone who’s been lucky enough to spend a career immersed in precisely what he loves to do.