Last week, after almost a year of anxious waiting, Massachusetts’ new Congressional district map was approved by the state Legislature.

The plan—which will go into effect with the 2012 election—was driven by the results of the 2010 Census, which showed significant population shifts across the country resulting in some states losing seats in Congress, and others gaining them. Massachusetts, which saw only a modest increase in its population since 2000, was one of 10 states to lose at least one seat; those seats, in turn, are to be reapportioned to states that saw significant population growth, most of them in the South and Southwest.

The Massachusetts map was draw up by a Special Joint Committee on Redistricting, co-chaired by state Sen. Stan Rosenberg (D-Amherst). It was a politically sensitive assignment, to say the least: the committee had to draw a new map that redistributes 6.5 million Massachusetts residents, currently divided among 10 districts, into nine. It had to make sure those districts were equal in population, and to group together so-called “communities of interest.” And it had to do so under the watchful eyes of observers with specific agendas.

Voters’ rights groups threatened to sue if the map didn’t include a minority-majority district in the Boston area. Incumbent members of Congress worried about holding on to their seats under the new plan, while government watchdogs insisted that the map should be a fair reflection of the state’s population, not a gerrymandered mess designed to protect incumbents. Locally, many worried that the new plan would give short shrift to Western Mass., which now has two Congressmen based in the region, by leaving just one seat to represent a diverse and geographically broad region.

The plan approved by the Legislature last week satisfies a number of those concerns. It adds more minority-majority precincts to the district now represented by Rep. Michael Capuano of Somerville, increasing the chances that the district will, someday, become the first in Massachusetts to elect a nonwhite member to Congress. It eliminates a number of the previous plan’s most glaring gerrymanders. It even creates one incumbent-free district, while forcing two incumbents into one single district—technically, at least. (While the new 10th District now includes the home towns of both Reps. Stephen Lynch, of South Boston, and William Keating, of Quincy, within a day of the plan’s release, Keating announced that he will move to his family’s second home on the Cape, to run for the seat in the new, incumbent-free 9th District.)

Here in Western Mass., the news isn’t great. As feared, the map leaves just one Western Mass.-based seat, pushing the Berkshires into a district anchored by Springfield, and shifting a number of Valley communities into a district based in Worcester. That move will weaken the region’s voice in Congress, and result in significant political changes in this end of the commonwealth.

*

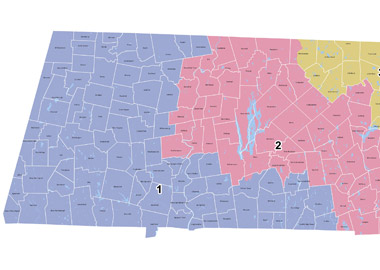

For years, Western Mass. has been home to two Congressional seats. The 1st District, represented since 1991 by Amherst Democrat John Olver, is the largest district, geographically, in the state, covering—for now—all of Berkshire and Franklin counties, much of Hampshire County, and parts of Hampden, Worcester and Middlesex counties, ending, at its easternmost point, in Pepperell. It’s a largely rural district, containing many of the smallest towns in the commonwealth. It’s also home to several small cities, including Pittsfield, Holyoke and Westfield.

The neighboring 2nd District covers much of Hampden and Worcester counties, meandering as far east as Bellingham in Norfolk County. While the 2nd also includes some small and rural towns, it’s dominated by Springfield, home town of Rep. Richie Neal, who served as that city’s mayor before moving to Congress in 1989. If Olver’s 1st District is regarded as a liberal bastion, Neal’s 2nd, while largely Democratic, leans more to the right, reflecting the blue-collar, socially conservative city at its center. Poised at the northern tip of the district are the Hampshire County communities of Northampton, Hadley and South Hadley, which ended up in the 2nd via some rather blatant gerrymandering, and which—in the case of Northampton especially—are a poor fit ideologically for Neal.

Under the new district plan, much of the existing 1st and 2nd will be merged into one district. Most dramatically—and to the dismay of many small-town residents—this new 1st District will include Springfield.

At public hearings held this spring and summer by the redistricting committee, some participants expressed fears that if Springfield—the third largest city in Massachusetts, with a population of 153,000—were merged with the small, rural communities that make up the 1st District, the needs of the smaller municipalities would be overshadowed. As Linda Dunlavy, executive director of the Franklin Regional Council of Governments, told the Advocate last summer, “[I]t does not make sense to lump Western Massachusetts into a single entity. … Hampden County and Franklin County are really different. Asking one congressional person to understand those vast differences would be a big disservice.”

Those concerns are warranted, agreed Matt L. Barron, a Democratic political consultant based in Chesterfield. “I think Neal will visit Berkshire County as often as Putin visits Chukotka,” Barron recently predicted. (For those without an intimate knowledge of Siberian geography, Chukotka is a peninsula in northeastern Russia.) The congressman, Barron speculated, might open an office in Pittsfield, but that would be mostly a token gesture.

“Neal is an urban guy,” he said. “He’s a former mayor. Springfield is his worldview.”

Neal’s office did not return a call from the Advocate. In a press release, the congressman said he was “pleased with the configuration of the new map,” adding, “Western Massachusetts is my home and I now will have the privilege of representing the entire region.”

Neal should be pleased. While his new district will lose some of the southern Worcester County communities he’s represented for years, he will gain several Western Mass. cities now represented by Olver, including Westfield, Holyoke and West Springfield—additions that will serve him well politically. Those cities, Barron noted, are demographically similar to Springfield: “They’re home to Reagan Democrats”—the kind of voters who form Neal’s political base.

Meanwhile, Neal will no longer represent Northampton, which will move into the newly drawn 2nd District. Barron chuckled over Neal’s public statements that he’ll miss representing that city.

“Northampton is teeming with liberals and activists and pro-choice people,” he said. “Northampton is the home of people who come down to Springfield and picket outside his office at the federal building: ‘Out of Iraq’; ‘We’re bombing poor innocents in Afghanistan.'”

Northampton, along with Greenfield and Olver’s hometown of Amherst, will now be part of a new 2nd District anchored by Worcester, home to liberal Rep. James McGovern. That change won’t force Olver into a primary battle with McGovern, however; shortly before the release of the new district map, the 75-year-old Olver announced that he’ll retire at the end of his current term.

In one sense, those changes make sense. For Northampton, McGovern is a better match than Neal; for Amherst, he’s not a dramatic change, ideologically, from Olver. It remains to be seen, however, whether the concerns of Valley communities will be heard or overshadowed in a district dominated by Worcester.

For McGovern, the changes appear unequivocally positive. The Valley towns he gains will offset the new, more conservative towns he’s also picking up in central Mass. McGovern now will also represent Valley towns with rich farm land, such as Hatfield, Deerfield and Whately— a good match, given his position on the House Agriculture Committee, Barron noted.

“McGovern is pleased as punch,” Barron said.

*

If the newly drawn districts benefit Neal and McGovern, they present more of a challenge to Neal’s expected opponent in next year’s Democratic primary for the 1st District.

Andrea Nuciforo, a former state senator from Pittsfield and now register of deeds for the Berkshire Middle District, has been planning a run for the 1st District congressional seat since 2009; indeed, he announced his plans long before anyone knew what the boundaries of that district would look like come 2012.

Until recently, it was generally expected that Nuciforo’s primary opponent would be Olver. The new maps, which will make Neal the 1st District incumbent, are bad news for Nuciforo, Barron said.

“I don’t see a path for him,” Barron said of Nuciforo’s chances.

While the newly drawn 1st District still includes important cities for Nuciforo—North Adams, his hometown of Pittsfield—Valley cities such as Holyoke, Westfield and West Springfield likely will favor Neal, Barron noted. “They offset all the little places,” he said. Meanwhile, neither Northampton or Amherst—both liberal communities where Nuciforo would likely do well—will be in the newly drawn 1st District.

After more than two decades in Congress, Neal is a political heavyweight who sits on the powerful Ways and Means Committee. He’s also a gifted fundraiser: according to Federal Election Commission records, Neal had almost $2.3 million in his campaign account as of Sept. 30—and that’s after spending $2.3 million in his 2010 race against Republican challenger Tom Wesley. “Now here we are: it’s 2011, and he’s sitting on $2.3 million,” Barron said. “It’s like he reloaded.”

Nuciforo, in comparison, had just $155,000 in his account at the end of September, including a $30,000 loan he made to his campaign. “That’s a very large gap to make up,” said Barron. And there’s not much time to do it: nomination papers for the 2012 election will be available in February.

Throughout the redistricting process, Nuciforo lobbied hard for the plan to include a 1st District made up of small towns and cities with populations under 50,000, all of which, he told the Advocate last summer, are “struggling to find their way in the new global economy.” Keeping those communities together would mean their specific concerns could be addressed in a way that they might not if they were lumped into a district with a large urban center like Springfield. Likewise, Nuciforo said in that earlier interview, “The city of Springfield needs and deserves a congressman focusing on the issues affecting that city and its immediate neighbors.”

A district like the one proposed by Nuciforo wouldn’t just benefit its residents, of course; it would also benefit his candidacy, by keeping together many of the communities he represented as a state senator—and keeping out of the district the political bigfoot Neal.

The new district map, then, had to be a blow to Nuciforo. Still, he offered a philosophical response: “There are some things that are within my control,” he recently told the Advocate. “Redistricting is not one of them.”

Nuciforo called the newly drawn 1st District “a very fair reflection of the terrain of Western Massachusetts. & It’s a very interesting mix of urban, suburban and rural communities. It includes communities that are both affluent and struggling economically.”

And, Nuciforo added, it’s a district that he thinks will respond well to his campaign. “I continue to think that the issue that is most important to voters these days are issues of social and economic justice,” he said. “Our progressive message of social and economic justice is one that should reverberate in this district.”

Nuciforo said he was disappointed that neither Northampton nor Amherst will be in his district—”I think that my progressive credentials voters in Amherst and Northampton would find appealing”—but expressed confidence that he can win next year’s race. “There will be between 55,000 and 60,000 votes cast in the newly configured 1st District, and they’ll be coming from all over the [district],” he said. “And we will work aggressively in every corner to earn the vote.”