Turnout at Springfield’s Sept. 20 preliminary election was dismally low: just 14.7 percent of voters cast ballots that day to narrow the field of three mayoral candidates to two, and the field of 13 at-large city councilor candidates to 10, in advance of the Nov. 8 general election.

But in the wake of that relative quiet, significant controversy has emerged about just what went on at the polls that day. A number of complaints have been filed with the U.S. Department of Justice alleging illegal and discriminatory incidents at several polling sites, largely affecting voters of color. The city’s Elections Commission calls those allegations overstated and, in some cases, simply false, while Mayor Domenic Sarno suggests the complaints are driven by political interests.

As Springfield heads into an especially important Election Day next week, the city finds itself debating important questions about the policies and politics that determine whether all voters are treated fairly at the polls.

Zaida Luna is the city councilor for Springfield’s Ward 1, which has a large Latino population. While the first-term councilor does not have a contested race herself this year, she spent the preliminary-election day observing at the polls in her ward—where, she says, she witnessed a number of problems, including would-be voters being turned away unnecessarily.

“People would come out and say, ‘I can’t vote because they can’t find me on the list,'” Luna said last week. “I’d say, ‘Go back in there. They have to give you a provisional [ballot].'” The next day, she said, she began getting calls from constituents reporting other problems.

In a letter to the Voting Section of the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, dated Oct. 20, Luna wrote that she “was shocked to see how widespread polling place problems were” at the preliminary.

“Record numbers of minority voters showed up at the polls on Sept. 20, but record numbers were also turned away for no good reason,” claimed Luna, who called on the Justice Department to send monitors to help at precincts with high minority populations at the Nov. 8 election.

Among the problems Luna reported: polling places that were not opened on time; the city’s 311 information line’s giving callers incorrect voting hours; voters being asked to show identification when they should not have been required to; voters not being offered provisional ballots in cases where they should have been; poll workers advising voters to cast ballots for or against specific candidates; and, in one case, a voter being handed a ballot on which Sarno’s name had already been marked. (Interestingly, a copy of that ballot shows that the name of City Council candidate Justin Hurst, the son of former School Committee member Marj Hurst and husband of current School Committee Vice Chair Denise Hurst, was also already marked, although Luna does not mention this in her letter to DOJ.)

In addition, Luna’s letter contends, Spanish-speaking workers and Spanish-language materials were not consistently available at polling places. In 2006, the Justice Department filed suit against the city for not providing adequate assistance to Spanish-speaking voters. The case was resolved with a consent decree in which the city agreed to hire more bilingual poll workers and provide election materials in Spanish, among other things.

While that consent decree expired last year, after the DoJ issued a notice that the city had met the terms of the agreement, the city is still legally required to provide bilingual materials and workers.

Luna’s complaints were echoed in a second letter sent to the DoJ by the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and the Boston-based Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Economic Justice. Luna had been put in touch with those organizations by Aron Goldman, executive director of the Springfield Institute, a progressive think tank, and a member of mayoral candidate Jose Tosado’s campaign team.

“It’s one thing after another,” Luna told the Advocate, explaining her request that the DoJ monitor the Nov. 8 election. “It’s not acceptable, and I know they’re going to need help.”

Even before she first ran for office, Luna said, she worked hard to get Latino residents to register and vote.

“I’m trying to educate Hispanics to go out there and vote,” she said. “It’s hard enough.” And when people do turn up at the polls and run into problems, she added, some of them will give up, never to return.

“Enough is enough. I’ve seen it myself for years and years as things like that go on and didn’t say anything,” Luna said. “Well, I’ve seen enough.”

The Justice Department has yet to say whether it will send monitors to Springfield next week.

*

Luna wasn’t the only one to field complaints about the Sept. 20 preliminary election. The Springfield branch of the NAACP also received calls about problems, specifically about voters being asked by poll workers to show photo IDs, without legal justification. On Oct. 21, the Rev. Talbert Swan II, the branch’s president, sent his own letter to the DoJ explaining the concerns and, like Luna, requesting federal monitors at next week’s election.

Requiring voters to show photo IDs has become a hot-button issue in recent years. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, as of September, seven states require voters to show a photo ID to vote, while in another seven voters are asked to show a photo ID but are allowed to vote without an ID if they can satisfy certain other requirements, such as providing their birth date or signing an affidavit attesting to their identity. Another 16 states require voters to present forms of identification but do not require them to be photo IDs; utility bills or bank statements with the voter’s name and address, for example, are acceptable.

The push to require voters to show ID is a recent one, the NCSL notes. Of the seven states with the strictest photo ID laws, five passed those laws this year. Twenty states that did not have voter ID laws previously at least considered them this year.

An effort to require Massachusetts voters to show government-issued identification at the polls was derailed, at least temporarily, in September, when the office of Attorney General Martha Coakley ruled that a proposed ballot initiative that would put the question before voters was unconstitutional. According to the AG’s ruling, requiring voters to purchase a state ID would violate the constitutional right to free elections. (While some states issue government photo IDs for free, Massachusetts charges $25 for non-driver photo IDs, and $50 to $75 for drivers’ licenses.) Proponents of the ID requirement have vowed to legally challenge Coakley’s ruling.

In an interview, Swan compared voter ID laws to “the poll tax of the old days,” another effort to use the law to keep minority voters away from the polls. “Studies have shown that as high as 11 percent of eligible voters nationwide do not have a government-issued ID. This percentage is higher for seniors, racial minorities, low-income voters and students,” he wrote in his letter to the DoJ.

“The demographics more likely not to have government-issued IDs are communities of color,” Swan told the Advocate. “I think those that are proposing [the laws] know that.”

Voter identification requirements, he added, aren’t the only political scheme being employed, largely by Republicans, to try to silence certain voters. Swan pointed, for example, to a recent unsuccessful effort in New Hampshire that would have banned college students from voting in their college town unless they or their parents were permanent residents of the community.

“Nationally, they are targeting anyone likely to vote Democratic, anyone likely to try to vote for President Barack Obama,” Swan said. “That’s of great concern to the branch and the national organization.”

Massachusetts voters can be required to show identification in some cases. Under the federal Help America Vote Act, passed in 2002, voters who register for the first time after Jan. 1, 2003, are required to provide identification; acceptable forms include a driver’s license or other government photo ID, a bank statement or utility bill, or a paycheck.

Voters can show this ID when they register in person; voters who register by mail can send in a copy of their ID. If they do not, they will be asked to show their ID the first time they vote in a federal election.

However, first-time voters who fail to bring identification to the polls can still cast provisional ballots, which will be counted if local election officials determine that they are eligible to vote. Similarly, voters who end up on the “inactive voter” list because they failed to return the most recent municipal census can cast a provisional ballot but will be asked to show identification.

In the days after the Sept. 20 preliminary, Swan said, the local NAACP branch heard of about 15 or 20 instances of problems involving voters’ being asked to produce identification. “There were poll workers turning people away, telling people you cannot vote if you can’t produce ID,” or failing to tell voters that they could cast provisional ballots, Swan said.

The complaints, he said, came from Wards 1, 4 and 5, all of which have large African-American and Latino populations. The NAACP also received reports of problems in Holyoke.

*

Like any election day, the Sept. 20 preliminary did not go off without a hitch, said Gladys Oyola, secretary of Springfield’s Election Commission. But she questioned whether there were as many problems as Luna and Swan contend, particularly in light of the low voter turnout.

Of the city’s 93,924 registered voters, only 13,804 cast ballots that day, according to Election Office figures. Turnout was especially low in the wards where the complaints were lodged: in Ward 1, 1,374 ballots were cast; in Ward 4, 1,130. (For comparison: 2,930 ballots were cast in the largely white, more affluent Ward 7.)

“The reality of this specific election day was that it was a slow day,” Oyola said last week. “That’s where I come back and say that the claims of the issues being so widespread raise red flags for me.”

The Election Office, Oyola said, has a system in place to deal with problems as they arise. In addition to the hundreds of poll workers, 64 police officers and a captain are assigned to the polls, runners travel among the polling sites fixing machines, delivering materials and generally troubleshooting, and extra workers field phone calls at City Hall. “There’s quite a few people out in the field who have their eyes and ears on the situation,” Oyola said. “How come I didn’t hear about [the alleged problems] as they were happening?”

There were, indeed, some problems at the polls that have been verified, she added. She offered, by way of example, a situation not included in Luna’s or Swan’s letters: at the polling place at the Mary Lynch School, at least one voter could not get in because the door had been accidentally locked. The voter banged on the door until a poll worker answered, and the door was kept unlocked after that, she said.

“Yes, some of those instances we were able to verify. For them to be considered widespread and egregious I don’t think is true,” said Oyola, adding that poll workers will be reminded about policies and potentially confusing issues for next week’s election. “We try to inform them of the correct procedures. That’s our first line of defense,” she said. The question of when voters should be offered a provisional ballot “was one thing we trained heavily on,” she added. “It’s really the responsibility of the clerk and the warden [at the polling places] to walk the voter through that procedure.”

Oyola suggested that some of the complaints might stem from observers’ limited knowledge of election laws and procedures. “There’s a lot of misinformation,” she said. “People who are working with the campaigns have informed themselves to & know kind of a piece of the puzzle. When it comes to a greater picture they’re misinformed.”

Swan offered a different perspective: that many of the problems stem from poll workers’ not knowing all the relevant laws and procedures, and misinforming voters. According to Oyola, all city poll workers are required to attend a training session when they’re first hired, and then again in years when new election laws have been passed. Returning workers can attend a refresher course, but are not required to. This year, she said, there were no new laws, and most workers were returning hires, so they did not have to attend training.

Swan, however, believes that all poll workers should be required to attend an annual training regardless of whether the laws have changed. Because they only work a couple of days a year, even veteran workers could benefit from a refresher, he said. “I think the poll workers don’t know [the law], and that goes back to proper training of poll workers,” he said.

*

While the allegations of problems at the Sept. 20 preliminary raise larger questions about voter access and fairness, they also can’t be divorced from the local political context.

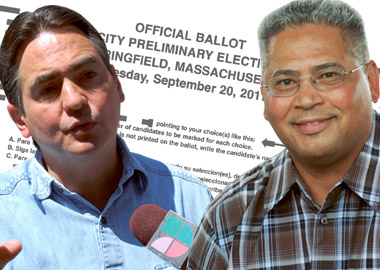

This election is an important one for Springfield in several ways. Starting with this election, the city’s mayoral term will be extended, meaning that whichever candidate voters choose on Nov. 8—Sarno or Tosado, the president of the City Council—they’ll be blessed with, or stuck with, for four years.

It could also be a historic election: if Tosado wins, he’ll be the first Latino mayor—indeed, the first mayor of color—in a city whose demographics are increasingly Latino and African-American.

Luna, a Tosado supporter, referred to the significance of his candidacy in her letter to the Justice Department. Tosado, she wrote, “is the first Latino candidate for mayor in the city’s history. While Latino turnout has traditionally been very low, we are hopeful that the numbers will increase because of this race. By contrast, the incumbent mayor does not have the same incentive to increase voter turnout among traditionally underrepresented groups. This is one reason we are concerned about the city doing all it can to remove barriers for minority, particularly Spanish-speaking, voters. We can bring voters to the polls, but we have much less control over what happens when they arrive.”

Sarno told the Advocate that he has “complete confidence” in Oyola’s ability to run a fair election. “She has been unprecedented in her outreach to all voters, especially in the Latino community,” he added.

As for reported problems at the polls, “some of the allegations are false, and some of them are completely exaggerated,” the mayor said.

“This comes four weeks after the election,” Sarno said. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s political posturing.”

Political posturing to benefit the Tosado campaign? “You connect the dots,” Sarno said.

Luna adamantly denied raising the issue to improve Tosado’s chances. “It’s not political,” she said. “It’s not because I’m supporting Jos?. I do it because people contact me [about problems they had at the polls]. They tell me, ‘Don’t expect me to go out there [to vote] Nov. 8. I’m not going to go through that [again].'”

Luna also disputed Sarno’s suggestion that she only raised her concerns as the general election approached, saying that she began fielding calls about problems the day after the preliminary but needed time to gather information and prepare her Justice Department letter.

During that time, Luna also discussed her concerns with Goldman, a strategist for the Tosado campaign. Like Luna, Goldman said his work to improve voter engagement, particularly among people of color, long predates his work with Tosado’s campaign. When Luna expressed her own concerns about problems at the polls, he said, they began comparing notes, with Goldman then beginning an ongoing conversation with Oyola.

“This has nothing to do with any campaign, or who people vote for,” Goldman said. “I’m just a policy guy who wants to see good things happen.”

On the preliminary day, Goldman visited several polling places in Ward 1. “I was amazed by how many different obstacles there were for voters,” he said, “particularly in minority communities.”

Those obstacles, he said, included people being asked for identification who’d never been asked to provide it before, or not being told that the ID did not need to have a photo; people being sent to different polling sites because they weren’t on the list at the first place they came to; people not being offered provisional ballots when they were legally entitled to them. Goldman said he saw some voters give up and walk away without voting—some because they needed to get to work, some because they found the process dauntingly confusing. “It’s sort of like going to the welfare office—the hassle factor,” he said.

What he saw at the polls, Goldman says, underscores larger problems in Springfield, where the reality of residents’ daily lives is greatly determined by race and class. “There doesn’t need to be any sort of conspiracy to block access,” he said. “If you look at these egregious disparities [at the polls] that, not coincidentally, mirror the disparities in the student achievement gap, mirror health disparities, mirror economic disparities, there’s all the evidence you need to know that something has to be done.”

Oyola—the first Latina or Latino to head the Elections Commission—said she understands the struggles to get underrepresented voters to the polls; she grew up in a politically active family, held campaign signs on Election Day as a child, and served as an aide to state rep Cheryl Coakley-Rivera, whose district includes Ward 1. Prior to her appointment as elections secretary, Oyola ran the city’s Spanish Language Election Program.

Luna’s claim that record numbers of Latinos were turned away at the polls, Oyola said, “is one thing that I did take personally. For about a half hour I stewed over it. Then I had to step back and say I had to understand the frustrations their campaign has and other neighborhood organizations have. I’ve been there.”

Swan expressed confidence in Oyola’s willingness to address the problems. “My sense is that she does get it,” he said. “My sense is that she inherited a system that needed to be fixed to begin with, that her office has faced some budget cuts and reduction in staff. But I think, overall, she’s committed to making sure that they’re in compliance. I don’t get the sense one way or the other that she’s running an operation that is trying to tip the scales in any particular direction.”

The NAACP is a politically neutral organization, added Swan, who focused on the specific allegations, not the Sarno-versus-Tosado subtext. “Whether political or not, these are credible concerns that need to be addressed, regardless of who the persons who are bringing the issue to the fore are supporting in the election,” he said.

With a number of high-stakes election in the near future—this fall’s mayor’s race, then, in 2012, a Senate contest and a presidential primary and election—”our concern is just that eligible voters are allowed to vote, and there are no unnecessary restrictions placed on them in order to cast a ballot,” Swan said.