Science fiction writer Philip K. Dick used to be considered, like most science fiction writers, a second-class (if prolific) inhabitant of the genre realm, forced to labor away outside the mantle of legitimacy worn by his “literary” cousins.

That is, to put it mildly, no longer true. It’s probably fair to say his wider recognition began with the 1982 film Bladerunner, based on his excellent novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Unfortunately, the film arrived mere months after Dick’s death at age 53. In the years since his death, Dick’s stories and novels have become source material for a slew of films—Total Recall, The Minority Report, Screamers, Paycheck, and A Scanner Darkly, among others—and his writing has made its way into plenty of college classrooms, even onto the roster of the Library of America series. He’s shown up in the musical world, too, notably in the lyrics of noisy visionaries like Sonic Youth.

Dick’s writing is not wildly stylized, but his concerns—what is real, and what is human—led him to create works that range from noirish explorations of grim futures to dark-tinged if amusing romps in which reality is a fluid concept. His books seem to reflect an endless searching for the truth of his own surroundings, his own reality. In his last years, that search took on new urgency when Dick experienced something dramatic and impossible to pin down, an episode that might have been psychosis, religious epiphany, alien contact, or something else entirely. He explored that matter in an 8,000-page (or more) journal, some of which has been published as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick.

I found Dick’s writing revelatory when it first came my way courtesy of a shrewd high school teacher. Something in Dick’s mixture of concerns philosophical, religious and futuristic revealed that science fiction need not just be kids’ stuff, not mere “space opera.” The more I found out about Dick’s complicated life, the more intrigued I became. Dick might have been mentally ill—he questions his own sanity in his writings—but also complicated the question through a fondness for drugs.

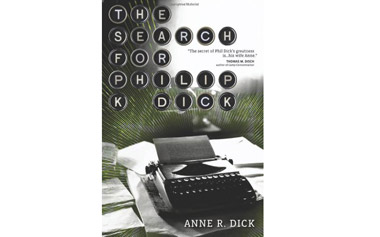

For fans of Philip K. Dick, researching the man leads quickly to the kind of reality-questioning maze he specialized in creating. It’s maddeningly difficult to get a handle on the real man. That effort got a major shot in the arm recently, with the Tachyon Publications edition of Anne R. Dick’s The Search for Philip K. Dick. The book was initially published in the ’90s without much fanfare, but Tachyon’s edition is an updated, fact-checked version that’s a pleasure to read.

Anne Dick was Philip Dick’s third wife (he married five times), and unusually involved in his creative process, serving as first reader for many works. Her prose in The Search for Philip K. Dick is often deft. What makes the book simultaneously enlightening and frustrating is that Anne seems, like many of Dick’s fans, to have fallen under the writer’s spell to such an extent that her search, like most everyone else’s, seems to arrive at the conclusion that knowing the “real” Philip K. Dick is an impossibility. Of course, writers have hardly cornered the market on cultivating a sense of inaccessibililty or rarefied otherness, but the cult of elusivity around Dick is remarkably strong.

Anne Dick writes: “He didn’t seem to have a fixed identity, or did he have several? … Phil was a psychic shape-shifter.”

Her prose is seasoned with an occasional whiff of near-hagiography, yet manages to reveal the everyday side of the writer, offering telling and prosaic details like Dick’s fear in descending a beach cliff with a rope. She slyly, perhaps unwittingly, delivers mystery about a mercurial man, but also offers an unflinching look at what her life with him was like.

At the end of the day, cult of elusivity or no, Dick was as human as anyone. His charismatic, if apparently frustrating, way with others hid an internal life of rich and imaginative contours. It may well be that the key to a clearer understanding of this unusual man is not through the reminiscences of those who were close to him, but in the reams of pages he crafted through those internal meanderings. All the same, he probably would have loved to know that his personality, almost three decades after his death, remains as hard to pin down as the shifting realities that fascinated him.