In 2002, Bristol County Sheriff Thomas Hodgson instituted what was, from his perspective at least, a successful new policy: he began charging inmates under his authority a daily fee of $5 to help cover the cost of their incarceration.

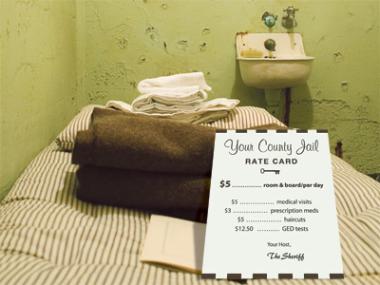

The policy—called the “Inmate Financial Responsibility Program”—also included fees for specific services: $5 for medical visits, $3 for prescription medicines, $5 for haircuts, $12.50 to take a GED test. The money came from prisoners’ “canteen accounts,” individual accounts used to buy incidentals like snacks and typically stocked by their families or significant others. Prisoners who qualified as indigent were exempt, and those who owed fees upon release would have their unpaid fees forgiven after two years—if they stayed out of jail during that time.

Hodgson described the program as a way to instill responsibility in prisoners. “Look, having inmates come to prison and telling them that you don’t need to worry about the costs associated with running the prison is, I don’t think, a good message for them,” Hodgson told the Boston Globe earlier this year.

Hodgson’s program collected about $750,000 in fees before it was halted in 2004, when a Superior Court judge, in response to a lawsuit filed by inmates, found that the sheriff lacked the legal authority to institute the policy.

Hodgson appealed the decision, and in January of this year, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld the lower court’s ruling, saying that it was the Legislature’s role, not the sheriff’s, to create such a policy.

Undaunted, Hodgson vowed that he would appeal to lawmakers to grant that authority to the sheriffs. Late last month, in the last-minute scramble of its budget process, the state House of Representatives passed a budget amendment that would allow the state’s 14 sheriffs to charge inmates a “daily custodial fee” of $5, as well as fees for certain medical and other services. A similar amendment is now pending in the Senate’s version of the budget; at deadline, the Senate had not yet voted on the measure. The fee system would also need the approval of the governor.

The House amendment passed with strong bipartisan support, by a vote of 93 to 62. To some supporters, the appeal lies in Hodgson’s notions of inmate responsibility; for others, it’s a more practical desire to raise funds for the state wherever possible. But critics predict that the policy will backfire, saddling inmates with debt that would make it that much harder to make a successful re-entry to society after their release. They also warn that prisoners’ families would end up footing the bill, adding an additional financial burden to families already under extreme stress.

Interestingly, it’s not just prison reform advocates who are critical of the bill. While a number of sheriffs from the eastern part of the state embrace the fee idea, it’s met with opposition from Valley sheriffs, including Hampshire County’s Robert Garvey, who described it as a “a terrible, terrible idea” that would, in fact, work against what he and other sheriffs are supposed to be accomplishing in their work with inmates.

*

The House amendment was sponsored by Rep. Betty Poirier, a North Attleboro Republican whose district includes Hodgson’s Bristol County, who described it as a way to save money for taxpayers.

The amendment allows sheriffs to charge inmates fees, including a daily room-and-board fee of no more than $5, plus $5 fees for medical and dental visits, $3 for prescriptions and $5 for eyeglasses. Exemptions are made for medical exams upon admission, emergency care, hospitalization, prenatal care for pregnant women, and treatment for contagious or chronic diseases. Inmates could not be denied medical care for lack of funds.

As in the system Hodgson had established in Bristol, prisoners who owe money upon their release would carry a debt that would be forgiven if they are not reincarcerated for two years after release. The law also calls for a process that would allow inmates to appeal fees. In addition, sheriffs who want to institute a fee system would need to prepare a report, to be approved by the Secretary of Public Safety, demonstrating its “financial feasibility.”

The Senate version of the bill, which was introduced by Sen. Steven Baddour (D-Methuen), calls for a similar fee schedule and includes the appeals and debt forgiveness provisions and a guarantee that inmates would not be denied health care for lack of money. In addition, it calls for a financial feasibility report, as well as annual reports to the Legislature detailing the program’s statistics.

Some backers of the bill are, no doubt, motivated by the notion that hard-working, law-abiding taxpayers are underwriting the plush lives of spoiled inmates—a notion Hodgson fed into in a 2009 interview with the Globe, where he disputed the idea that most prisoners are poor.

“In fact, we have some that leave our facilities in limousines,” the sheriff said. “If they have money to buy candy and cookies and higher grade sneakers . . . it is my belief they certainly have enough money to first pay for the cost of their care.”

Even stripped of such rather inflammatory images, public debate over a prisoner-fee system relies on a financial argument. Indeed, Republican gubernatorial candidate Charlie Baker has included it as one of his “Baker’s Dozen” list of reforms that he says would save the commonwealth $1 billion. Baker calls for charging “a nominal daily room and board fee” to inmates both in state and county facilities (the House amendment applies only to the county facilities run by the sheriffs). Baker also proposes that “inmates [who] are unable to pay should have their bills forgiven for good behavior after they are released.”

Baker’s campaign materials claim his idea would generate $10 million to $40 million but don’t specify how that wide-ranging figure was reached.

*

Across the country, struggling governments are turning to the criminal justice system as a source of potential revenue. “There is a trend in the states to add more categories of fees, and to raise the amounts of existing fees,” Rebekah Diller, a deputy director at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, told the Advocate. Often, she added, these policies, much like the amendment passed by the Massachusetts House, come about as a quickly hatched effort to save some cash, with little if any thought about what she called the “hidden costs” of imposing these fees of a population that’s already overwhelmingly poor.

This summer, the Brennan Institute will release a report looking at the national trend toward increasing fees in court and prison systems. The institute has already looked at policies in individual states, including a March study, authored by Diller, on court “user fees” in Florida. That state, the report notes, “relies so heavily on fees to fund its courts that observers have coined a term for it—’cash register justice.'”

In Florida, which provides no exemption for the indigent, the fees are often uncollectible, according to the report. Those who fail to pay the fees also face more penalties, including added fines or a suspension of their drivers’ licenses, which makes it harder for them to find or keep a job.

“At their worst, collection practices can lead to a new variation of ‘debtors’ prison’ when individuals are arrested and incarcerated for failing to appear in court to explain missed payments,” Diller’s report found.

The purported financial benefits of these kinds of fee systems can be undercut by administrative costs, Diller told the Advocate. “You end up spending a lot of money just to collect these fees,” she said.

You also end up creating one more weight around the neck of a newly released prisoner trying to re-acclimate to life outside, she added. “When you burden someone with debt coming out of prison, it’s yet another barrier to successful re-entry, and yet another factor that can contribute to recidivism. Very often you create a debt that won’t be paid but stays with the person and has consequences.”

*

In Massachusetts, prisoners’-rights advocates are braced to fight a new prisoner-fee system. The American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts has a number of objections, said communications director Chris Ott, including constitutional concerns about applying it to current inmates who’ve never had to pay the fees in the past. “It would essentially amount to a second punishment,” Ott said.

In addition, he said, since most prisoners would end up paying the fees from accounts funded by their families, “it amounts to a sort of back-door tax on those families.”

Lois Ahrens, director of the Northampton-based Real Cost of Prison Project, calls the House budget amendment “bad in every way.”

Most people locked up in county jails, Ahrens noted, are categorized as “presentenced”; they’re awaiting their day in court there because they couldn’t make bail. “They’re there because they’re poor. If they weren’t so poor, they wouldn’t be there,” she said. “And then to top it off, they could end up with $150 a month they’re being assessed.”

The budget amendment, Ahrens said, was a rush job; it includes no provision for how debts owed by inmates upon release would be collected, and it’s not backed by any documentation supporting the purported financial benefits.

Activists have spent years pushing reforms aimed at making it easier for released inmates to find a stable, productive path after prison, such as efforts to reform the criminal record system, commonly known as CORI. What small advances have been made would be dramatically undercut if the House budget amendment becomes law, Ahrens said. “These things are not separate issues,” she said. “It will hurt people and then slow down any tiny, tiny progress.”

Ahrens compared the amendment—with its quick passage and absence of debate about its larger consequences—to mandatory minimum sentencing laws that passed decades ago on a wave of tough-on-crime sentiment and that have since been widely recognized as failed policies.

“This is a perfect example of one of these horrible, bad, punitive ideas that end up causing negative consequences forever, that could happen overnight with no one knowing about it, and then it takes 30 years for us to undo it,” she said.

*

If the inmate-fee system does become law, it will be thanks, in part, to the hard-line sentiment that once buoyed the mandatory sentencing laws. In a recent article in the Quincy Patriot-Ledger, Hodgson, the Bristol sheriff, described arguments that the fees were unfair to inmates as “red herrings.”

“Nobody ever says, ‘What about the poor taxpayer who’s being victimized and didn’t do anything?'” Hodgson told the newspaper.

In the same article, Norfolk County Sheriff Michael Bellotti—who’s president of the Massachusetts Sheriffs’ Association, and who supports the fee system—said the proposal has the support of a “vast majority” of the commonwealth’s 14 sheriffs. But that majority does not include Hampshire County Sheriff Robert Garvey, who described the policy as “very shallow thinking.”

“I think it’s very shallow thinking to think that the people who are here, number one, can afford [the fees],” Garvey told the Advocate. “Most of the people that I encounter in this facility usually come from the very lowest part of our socioeconomic climate.”

Even more important, he added, the fees would really be a burden on inmates’ families. “It’s going to be taking away from them, and they are already in a poverty situation,” he said.

“It’s easy for legislators to pass this law who have not been witness to what goes on in these facilities,” Garvey added. “Obviously, in this political climate, it’s easy to be hard on anyone—’lock them up and throw away the key.’ Nobody has told the Legislature that the population we’re dealing with doesn’t have any money [or] they wouldn’t be here.

“People who have money don’t go to jail,” Garvey added; they have the money to make bail and hire attorneys. “We might read a lot about their crimes, but they don’t actually spend any time locked up.”

Legislators may be out of touch, but what about his fellow sheriffs who support the idea of inmate fees?

“I think it’s based on philosophy, to be honest with you,” Garvey said. “I think people are sent to us as punishment, not for [further] punishment. … Their penalty, obviously, is the loss of their freedom coming here. This [fee system] is double jeopardy to me.”

Garvey sees his role as preparing inmates for a productive life after their release.

“People don’t like to hear me say this, but there are an awful lot of people incarcerated here who are already victims of our society,” he said. “We have to provide an environment where change can take place, to provide opportunities to change so when we release someone they’re in better shape than when they came [here]. … That philosophy is not shared by all the sheriffs in the commonwealth.”

It is shared by Hampden County Sheriff Mike Ashe, who also opposes the fee proposal. “We really see it as an impediment to successful community re-entry,” said Rich McCarthy, spokesman for Ashe’s department. “With everything else that works against an individual as he’s trying to re-enter society successfully, if he’s got this other debt, it’s a tremendous financial challenge. For someone to return to their family and try to be self-sustaining and support their family, to add this on just makes it that much more difficult.”

Inmates already have jobs, working in areas like food service, maintenance and the jail laundry, McCarthy added. Through that work, he said, “they are accomplishing the very things this bill would want to accomplish. They are paying for their room and board by providing work, very needed work. … That’s accomplished without loading on this extra debt.”

In addition, inmates who hold community-based jobs through the prelease program already pay 15 percent of their wages toward their expenses.

McCarthy also questioned the creation of fees for medical appointments, which would create a disincentive for inmates to get care. (According to the Globe, when Hodgson began charging fees in Bristol, inmate medical visits dropped from 350 a month to 100 a month.)

Many people who end up behind bars have not had proper health care, McCarthy said; for them, the corrections system represents an opportunity to finally deal with long-neglected medical issues. “Incarceration actually becomes a chance to save a lot of health difficulties for these people, and resulting health costs in the community,” he said.

The Hampden Sheriff’s Department, McCarthy said, might have a reputation as progressive, “but we don’t have our heads in the clouds. … If we thought it was going to be an effective, sensible measure, then we’d support it.” But the department already looked into the idea of charging fees years ago, he said, and concluded it would be counterproductive. “It’s not practical, it’s not effective, it’s not going to produce the results people would hope it would. …

“There’s nothing sinister about this bill,” continued McCarthy. “The goal of everyone is that offenders become productive citizens of society—contributing, productive, paying, if you will, citizens of society. … But examined under the light of whether it would be effective or not, the real fiscal truth of it, then you see that it is not going to contribute to inmates being paying, positive, productive members of society.”

Diller, of the Brennan Center, agrees. “These budget gimmicks are very appealing on the surface, and when states are cash-strapped it can be very hard to fight them,” she said. “But when people think it through, think about the limited money that it could raise and the problems down the road, they start to reconsider.”