"The business of a newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."

The above maxim, adopted by many in alternative publishing, originated as part of a satire written by a Chicago Tribune writer in the early 1900s. He meant it as a tongue-in-cheek poke at the power of newspapers in general, and especially the newfangled investigative journalism that was beginning to appear in smaller papers around the country. He believed these "muckrakers" were making much ado about nothing.

Still, the quote works well to describe the aim of alternative journalism.

At 35, the Valley Advocate continues a long and rich tradition of reporting on the stories that local politicians, business leaders, bullies and cheats would prefer left untold.

Similarly, we have inherited the same scorn and ridicule the influential and wealthy have always heaped on those who attempt to speak truth to power and advocate change.

As we head ever deeper into an era of streamlined, consolidated and easily digested news, it's useful to understand the origins of the Valley's only free and alternative publication. As with those who came before us, we're not around to please the powerful. The more severe the sneer and hairier the eyeball the connected crowd casts upon what we print, the more certain we are that we're getting it right.

The following is a brief overview of some of the key publications and luminaries our paper is proud to consider part of our heritage.

Socrates—399 BC

By inventing the Socratic method of inquiry, the guy turned speaking truth to power into an art form. Instead of just sharing his technique for asking questions to illuminate hidden truths with his philosophy students, he tried his methods out in the field on test subjects. He argued that his interviews with the politicians revealed the corrupting influence of power: while the powers-that-be might have known a lot about some things, they'd become blind to what they didn't know. They had him commit suicide and tried to erase his teachings.

Martin Luther—1546

It was common practice for the Roman Catholic Church to sell pardons to sinners. So when a fund drive started to build a fancy new place of worship, as a matter of course, the church leaned on their pardon-marketing clergy to put a serious squeeze on the wicked. Clergyman Luther, though, published his 95 Theses, challenging Rome. The 86th thesis stated, in part, "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?" He was excommunicated.

Galileo—1632

With a telescope he built himself, Galileo scanned the heavens and saw things no one else ever had: sun spots, mountains on the moon, and the moons of Jupiter. He also began to see evidence that what Copernicus had said a century earlier was true. The Earth was not the center of the universe, much less the the solar system. The pope asked him to recant his findings. He replied, "I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with senses, reason, and intellect has intended us to forego their use." He was put under house arrest for the remainder of his life.

Thomas Paine—1776

After trying to rouse the rabble in England in 1772 by distributing a pamphlet on workers' rights, Paine found himself destitute. A meeting with Benjamin Franklin convinced him he should move to America in 1774. Two years later, he published "Common Sense" anonymously. 120,000 copies of the pro-independence pamphlet were sold in three months, and he became known as the father of the American Revolution. George Washington read his work to the troops before battle, and the French brought him to Paris to help jump start their revolution.

The Birth of Investigative Journalism—1900

By the turn of the century, newspapers had become big business in America. Competition was fierce, and all kinds of tactics were being tried to increase readership. As the major papers tried to outdo one another with their scandal-mongering and sensationalism, several smaller presses began taking advantage of new printing and distribution technologies, and they began publishing papers that tried to restore dignity to journalism. Instead of skimming across the surface of the news, they dug in deep. "Muckracking" was born.

Ida Tarbell—1902

After her father had lost his small oil refining business to larger interests, she began investigating the business practices behind big oil. In 1902, she began a series of interviews with Henry H. Rogers, the senior director at Standard Oil. Possibly not understanding her intentions, he was remarkably forthright about his company's shady dealings. The interviews were published in the magazine McClure's later that year. In 1904 the series was published as a book, The History of the Standard Oil Company. Seven years later, the company's monopoly was broken by Congress.

Upton Sinclair—1906

Before being published as a best-selling novel, The Jungle appeared in serialized form in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason. In horrific detail, the book described the Chicago meat packing industry from the point of view of a worker at the plant. The book was an immediate success and was partly responsible for the Pure Food and Drug Act passed that year. Sinclair, though, always felt the public had missed the point. He was less interested in the animals' welfare than the plight of the workers: "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."

The Masses—1911

Published monthly, The Masses was less about investigative journalism than about taking aim at American politics, art and culture through a radical, socialist lens. Like the alternative weeklies that appeared in the 1960s, the magazine featured a bold graphic cover and story titles usually depicting social injustice or lampooning the establishment. In 1917 the U.S. Postal office refused to mail the magazine to subscribers, and it, along with several other socialist publications, was forced to close.

Alternative Is Subversive From 1917 to 1950

The First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Great Depression made it difficult to be a radical in America. Instead of being hungry for social change, many were simply hungry. It was nearly impossible to have a nuanced view of socialism, because everyone "knew" that leaning to the left politically really meant you were a communist. In 1919, President Wilson authorized his Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, to conduct raids on the radical left, arresting them and deporting them. Alternative journalism, such as it was, mostly appeared in niche political journals and circulation numbers dropped considerably.

George Seldes—1940

When he began his newsletter, In Fact, Seldes had been a reporter for nearly 30 years. He was no stranger to controversy. An exclusive interview he had with the head of the German army after WW I was suppressed, and he was court martialed. Lenin expelled him from Russia, and Mussolini sent him packing from Italy. Eventually he quit the Chicago Tribune and published a book of writings they had suppressed. In Fact was started in the same spirit: taking on stories the mainstream was scared of covering. One of his first issues drew a connection between cigarettes and cancer, decades before it was fashionable to condemn the habit. The publication ended after he was blacklisted.

I. F. Stone's Weekly—1953

"All governments lie, but disaster lies in wait for countries whose officials smoke the same hashish they give out." Picking up where Seldes left off, Izzy Stone's weekly newsletter featured hard-nosed investigative journalism. He scoured the public record and utilized obscure official documents as his sources, often finding discrepancies and contradictions. During the Vietnam War, his reporting on America's movements became essential reading for other journalists. When he was forced to retire because of heart problems, he learned ancient Greek and wrote a book on the death of Socrates, arguing that the philosopher intended it as a willful political act.

Village Voice—1955

Originally funded by the author Norman Mailer, The Village Voice launched originally as a paper covering Greenwich Village, but soon extended its reach to the rest of New York City and beyond. In many ways it is the prototype for the alternative weeklies that began in the 'sixties and 'seventies. While it had Pulitzer-winning investigative journalism, it combined news with serious arts coverage and humor. Early on, it began supporting alternative theater by presenting the annual Obie award. The paper continues today, though a recent takeover by publishing conglomerate New Times Media has made some question its commitment to alternative values.

The Realist—1958

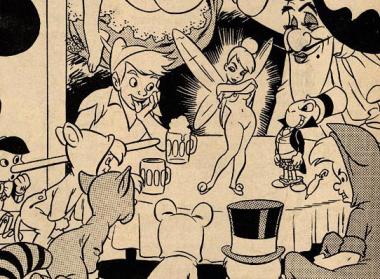

Paul Krassner started his seriously subversive magazine in the offices of Mad magazine. The Realist provided an attitude and style that became fundamental to the alternative press. Its chief tool was scathing satire. One issue included a red, white and blue bumper sticker with "Fuck Communism" on it; Krassner recommended that if anyone got flack for sporting it on their vehicle, they should tell the offended to "Go back to Russia, you commie-lover." Shortly after Disney's death, the magazine featured a center spread entitled, "Disneyland Memorial Orgy," featuring beloved animated characters getting it on.

"The Freep"—1964

The Los Angeles Free Press is considered by many to be the first '60s underground paper, and its politically charged coverage of the 60s is often credited with contributing to the end of the Vietnam War. Many of the hippie luminaries and activists from that era either contributed to the paper or were covered by it. Ron Cobb's underground comics (that influenced artists such as R. Crumb) started in the paper. The Freep helped found the Underground Press Syndicate, which participated in launching nearly 600 similar papers across the country.

Rolling Stone—1967

Jann Wenner started the magazine in San Francisco, citing a need for a publication that celebrated counterculture music, art and lifestyle. It was initially a lot less political than the underground press. This changed in the 'seventies, especially when the likes of Hunter S. Thompson joined the editorial ranks. Most of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas first appeared there in serialized form. The magazine also first introduced authors Cameron Crowe, Joe Klein, and P.J. O'Rourke. While still political, the magazine now features stories on mainstream pop culture and celebrities more often than not.

Alternative Feminist

Publications—1970

On the heels of the anti-war movement, a number of feminist publications sprang up in the early 'seventies. Ain't Me Babe started in Berkeley, the first of the underground press' feminist papers. It only lasted a year, but in Washington, D.C. the same year, off our backs began, and it's still running. Since its inception, the magazine has been edited and published by a collective of women using consensus decision making. In 1972, co-founders Gloria Steinem and Letty Cottin Pogrebin began Ms. magazine, which, like Rolling Stone, seemed to struggle between its activist message and its commercial interests.

Valley Advocate— 1973

1975 and Beyond

During the last quarter of the 20th century, dozens of alternative weeklies sprang up across the country, building on the politics of the 'sixties and borrowing the publishing models of that era. As the Internet continues to nibble away at the readership of dailies, some believe the alternative press, with its emphasis on local news and arts, is better positioned than most mainstream publications to survive. Whether or not this is true, though, hinges greatly on whether or not those who read the news are interested in more than what their leaders are telling them. Time will tell.